Looking through the Trees

When an autistic 11-year-old on his bike went missing with his dad’s rifle this past August, Alaska State Troopers had a problem. They couldn’t activate their normal search-and-rescue protocols because a gun was involved; they didn’t want to take a chance of putting search crews in danger. They instead called the University of Alaska

Fairbanks (UAF) for some unmanned aircraft backup.

The boy’s family lives in a thickly wooded area on the north edge of Fairbanks. Troopers knew they’d have a hard time locating the youngster if he didn’t want to be found. They discovered his abandoned bicycle and a probable campsite, so they believed they were on the right track, but blindly scouring the dense forest on a rainy day didn’t seem like the best way to search. So they contacted the university’s Alaska Center for Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration (ACUASI, http://acuasi. alaska.edu/) to ask if it had an aircraft with thermalinfrared capability available.

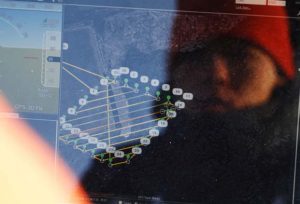

Pilot Nick Adkins took the initial call. “We knew we’d want to support their search, so we started getting our gear together right away,” Adkins says. ACUASI Director Cathy Cahill agreed immediately. ACUASI’s airspace expert, Tom Elmer, got on the phone to the local Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) office to request the necessary authorizations, while pilots Adkins, Trevor Parcell, and Karen Bollinger assembled the components to fly a Ptarmigan UAS (unmanned aircraft systems), a hexacopter system initially developed by UAF engineering students. Once they were on the scene, Adkins and Parcell programmed the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) to fly a grid over the area in which the troopers thought the boy might be, looking for heat signatures, while troopers searched on the ground. Bollinger acted as observer, spotting for hazards.

By looking at the data coming in from the UAV, the troopers determined fairly quickly that the boy was not in the area in which they were searching and expanded their efforts elsewhere. “Basically, by looking at heat, we were able to determine he wasn’t where they thought he was,” says Cahill. This allowed the troopers to move to the next search area, saving precious time and manpower. Although they didn’t find him—the boy was returned home safely later that evening, picked up by a passing motorist—Cahill points out that this situation provided a good opportunity to demonstrate the usefulness of

unmanned aircraft technology.

Corey Upton of Northern Embedded Solutions takes a break in the winter sun next

to a Ptarmigan UAS during flight testing at the Cold Regions Test Center at Fort Greely,

Alaska. (Photo courtesy of ACUASI )

ACUASI and the Ptarmigan

Law enforcement and other public agencies have called on ACUASI for help before. The center has used UAS to help map crash scenes, demonstrate capabilities in active shooter training scenarios, and chart fire boundaries for wildland firefighters.

The program originated in 2001, but ACUASI was officially established in December 2012 by the University of Alaska Board of Regents in recognition of the importance and growth of the unmanned aircraft industry. ACUASI, part of the UAF Geophysical Institute, leads all UAS programs for the entire Alaska university system. In 2013, ACUASI was selected by the FAA to lead one of six test sites established by the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012. The ACUASI-led Pan-Pacific UAS Test Range

Complex includes principal partners in Oregon and Hawaii as well as 56 nonstate partners located across the United States as well as internationally. Ranges are located in the states of Alaska, Oregon, and Hawaii and in Iceland.

UAF students have been key players in the program from the beginning. The Ptarmigan, ACUASI’s workhorse UAS, was initially developed in 2012 by two engineering students

on a fellowship grant from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Logan Graves and Ben Neubauer started with a DJI S800 hexacopter frame. “We stripped out

all the guts and installed an APM 2.0 autopilot so that we could modify all the source code,” Graves says. Neubauer’s skills in both circuit-board and 3D design were invaluable. They modified the frame to hold various payloads, depending on the task at hand. “Basically, we made a checklist of the things ACUASI wanted,” Graves says. “We went with a systems design: buying off-the-shelf components and integrating them into a larger package” to maximize flexibility and keep costs under $10,000.

Initial development of the Ptarmigan took about a year, but it has continued to evolve. Three UAF engineering grads (originally including Neubauer) formed their own firm, Northern Embedded Solutions, and developed a number of sophisticated Ptarmigan payloads for particular ACUASI projects. The Ptarmigan has been used for proof-of-concept projects, including vegetation surveys over Arctic tundra, observations of test burns of crude-oil spills on water, bridge inspections, surveys of spawning salmon river habitat, observations of sea grass and sea otters, topographic mapping of nearshore sea ice on the Beaufort Sea, pipeline surveillance, and research to determine how walrus respond to the noise made by unmanned aircraft during population surveys.

The backbone of the Ptarmigan system is a custom integration board that communicates commands between the autopilot and the aircraft motor, landing gear, and payloads that may need to communicate directly with the autopilot. The Ptarmigan uses GPS to determine its location and navigate to its intended destination. It is a general-purpose aircraft designed for flexibility in both payload and avionics; the flexibility of the platform quickly made it one of ACUASI’s most-used systems for

accomplishing a variety of missions. The group keeps four Ptarmigan frames ready to configure for particular applications. They also use several other platforms, such as the Aeryon Scout and ScanEagle.

Karen Bollinger, Tom Elmer, and Nick Adkins back at ACUASI after a successful mission. (Photo courtesy of ACUASI )

Quick Response Was Key

“The really cool thing was how fast we were able to respond to the request for help” in searching for the lost boy, Adkins says. The team was on scene in less than an hour, ready to launch. The FAA office in Fairbanks knows Elmer well and is very familiar with ACUASI’s operations, so it quickly issued the appropriate Certificate of Authorization, giving ACUASI permission to fly that day even after dark and under less than- normal visual-flight-rule thresholds. Light rain had been falling throughout the day, but as the mission began, the clouds were breaking up; by the time the team was on site, they had good flight conditions. “We have a lot of times where we’ve got search-and-rescue where we’re looking with eyeballs and helicopters flying around but you can’t see through foliage,” trooper Thomas Mealy says, in an article that appeared in the “The [UAV-mounted infrared] was a capability that we could actually see, through the foliage, what was…on the ground,” he says. “It was really a great capability that I think we’ll have a lot of applications for in the future.”—LJ Evans