An honest review of the Skydio 2 must actually be two reviews: one that compares the aircraft with its own potential, and the other that compares it with other aircraft that can be had for a similar price to perform general aerial imaging missions. Whether the Skydio 2 is an astonishing success or a quirky outlier actually depends more on the goals of the end user than it does the characteristics of the aircraft itself.

Regardless, the basic facts are the same, so here they are: the main camera—the one that actually captures video and still images—incorporates a Sony IMX577, capable of shooting 4K video at 30 frames per second (FPS) or HD video at up to 120 FPS in addition to 12 megapixel stills. On paper, that is a fairly typical set of specifications for a drone at this size and price point. However, Skydio wrings the most out of every pixel. The images are vibrant, and even without activating the camera’s high dynamic range (HDR) capability, it does a remarkable job of balancing the lighting across a scene. For example, if you put the horizon line across the center of the frame, you will immediately notice that both the sky and the ground are still visible, without being over- or under-exposed.

The Basics

The Skydio 2 has six 4K cameras, each with a 200-degree field of view. Together, they create a complete picture of the operating environment in every direction, generating 45 megabytes of data 30 times per second to drive its remarkable collision avoidance system. In short, it literally sees everything, and yet the Skydio 2 is so narrowly focused on the single goal of being a perfect flying action camera that comparisons with other small, civil UAS are problematic.

At a Glance

Name: Skydio 2

Manufacturer: Skydio (skydio.com)

Type: Autonomous Aerial Imaging Platform

Size: 223 x 273mm

Weight: 775g

Flight time: 15 min.

Camera: Sony IMX577 12.3MP CMOS, 4K/30 FPS Video

Price: $999.00 (basic package)

The camera is slung on a front-mounted gimbal—like the Parrot Anafi—so that no part of the aircraft hangs over it. However, it does the Anafi one better by providing three-axis stabilization. With this configuration, the Skydio 2’s camera could, in theory, pitch all the way from zenith to nadir. However, it stops at 45 degrees above the horizon, limiting its use inspecting the underside of a bridge deck, for example. That isn’t a problem if what you want is a flying action camera, not a general purpose small, civil uncrewed aircraft system (UAS).

The airframe feels very sturdy, no doubt because of the magnesium skeleton beneath its distinctive blue and black plastic skin. It gives the aircraft a refined feel in the hand, like a high-end laptop, but the real reason for this choice is to support the collision avoidance system. In order to function, the system must know the precise distance between each of the cameras. The flex in a plastic airframe, for example, would be enough to degrade its performance.

That’s why the Skydio 2 does not fold down for travel or storage, like virtually every other UAS in its size category: an airframe movable limbs, for example, would not provide sufficient rigidity and precision to make the system reliable.

The controller, sold as a separate accessory by Skydio for $149, is actually a re-branded SkyController 3 developed by Parrot, which originally shipped with its Anafi drone.

Hot! Hot! Hot!

The technical specifications for the Skydio 2 read like a gaming laptop, with a main processor, 256-core GPU and a CPU, as well as four gigabytes of 128-bit RAM. That much computational firepower is required to push through one million data points in three-dimensional space every second and, like a gaming laptop, it builds up a lot of heat in the process.

After each flight, the body of the Skydio 2 is very nearly too hot to handle comfortably. That’s enough to make me worry about losing the aircraft to overheating. However, the company claims a maximum operating temperature of 104 degrees Fahrenheit—comparable to other drones in its class. So, I suppose we’ll have to take them at their word on this point.

Power is supplied by a rechargeable, three-cell, 4280mAH LiPo battery which in real-world testing delivered about 15 minutes of flight time. That isn’t bad, but it is a little below average for an aircraft of its size and performance. The battery bears further consideration for several other reasons, as well.

First among these is the magnetic retention system, which is extremely cool. Position the battery near the cavity on the belly of the aircraft and it snaps into place with a satisfying click and reassuring certainty. Why other manufacturers have not embraced this approach is a mystery, because it’s awesome.

That said, there are some drawbacks to the Skydio 2’s battery system. First, the battery serves as the aircraft undercarriage—the sole point of contact between the airframe and the ground. This makes it prone to leaning in one direction or another if not placed on a flat surface, unlike other aircraft with a wider base of support. Also, given the fact that a LiPo battery can burst into flame and emit toxic smoke if damaged, making it the first point of contact during a rough landing or a crash seems like a bad idea.

Second, the battery can only be charged using the drone itself as the charger. That means taking it out of its protective case and clearing space on your desk for the whole aircraft just to charge the battery. This has operational implications, as well, because you can’t recharge one battery while you’re flying with another.

Also, and this is downright peculiar, when a battery is finished charging you can’t simply put on the next one. You have to disconnect and reconnect the power, as well, or the battery won’t take a charge.

For an extra $129—a non-negligible percentage of the base aircraft price—Skydio will relieve you of this burden with a separate two-battery charger.

The Skydio 2 incorporates a magnesium alloy chassis that provides the airframe with strength and rigidity, but it still weighs 775 grams—less than the Mavic 2 from DJI.

Designed by GoProfessional Cases, Skydio sells a rugged, waterproof case to protect the aircraft and its optional accessories—either as part of its pro kit or as a separate item.

Ground Control

It is worth noting that the Skydio 2 base package does not include a hand-held controller, but instead relies on your smart phone and a pair of virtual joysticks for direct input—not my favorite control interface. For $149, Skydio is happy to sell you a controller, which will look very familiar to Parrot Anafi pilots: the SkyController 3.

Personally, I’m a fan of the SkyController 3: it’s simple and sturdy, and it uses a lever instead of a dial to control camera pitch. On the downside, the smart device clamp isn’t quite large enough to accommodate my Galaxy Note 10+ in its protective case—although it fits with the case removed.

One change you will notice from the Parrot version of the controller is that the standard USB port has been removed. Indeed, you won’t find a single standard USB port in the entire Skydio 2 ecosystem. Instead, it relies completely on USB-C connections. Personally, I’m a big fan of USB-C, but even I’m not sure that the company’s universal implementation of the standard is a good choice.

As a drone pilot, a smart phone user and a human being living in the early decades of the 21st century, I’ve got tangled piles of USB cables strewn about my home: all of them standard USB to micro-, mini- or C-type connectors. The one thing I didn’t have before the Skydio 2 arrived is a USB-C to USB-C cable.

One is included with the kit, but it’s too long and heavy to use comfortably with the controller and my smart phone, so I purchased an extra one online. It wasn’t a huge expense, but the point is you aren’t as likely to have a lot of spare USB-C to USB-C cables lying around if you suddenly find you need a backup—and that can be a problem with a mission critical item.

And while we’re on the subject of mission critical items, make sure you add a MicroSD card to the list. One is not included with the basic kit, which is ironic because the app will not let you take off unless one is installed. I appreciate my aircraft giving me a reminder that I don’t have a memory card installed, but prohibiting me from flying without one is another matter entirely. It’s not hard to imagine this requirement tripping up first responders who might urgently need an aerial perspective but don’t necessarily need to capture video or still images.

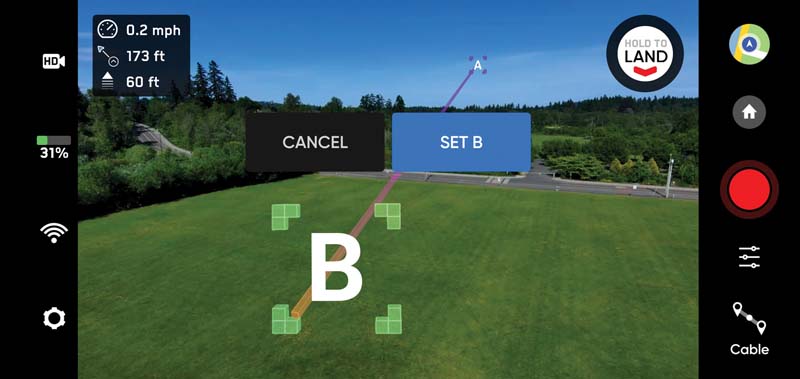

The Skydio 2 makes good use of augmented reality, as seen here in cable-cam mode, to illustrate its autonomous flight maneuvers.

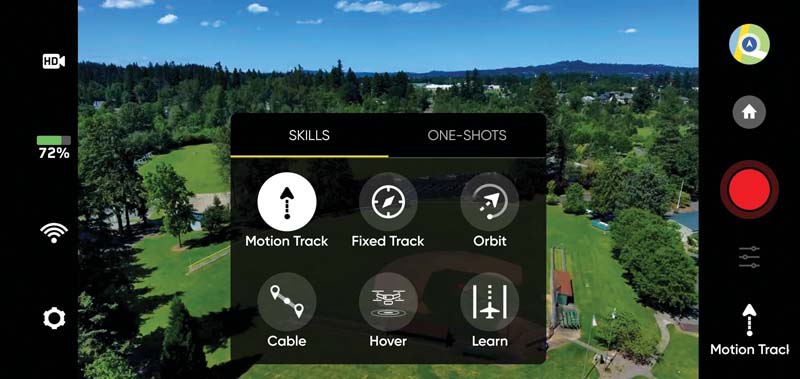

The Skydio 2 offers a library of pre-programmed flight maneuvers, divided into two categories: skills and one-shots. Skills include its extraordinary follow-me capabilities, while one-shots include classics like the dronie.

The Skydio 2 app provides a bare minimum of telemetry from the aircraft—speed, distance and altitude—and even these can be disabled within the settings menu. It can be a jarring change for experienced drone pilots who are accustomed to having a wealth of flight parameters at their disposal.

A controller does not come standard with the base Skydio 2 kit, meaning that pilots will need to rely on virtual joysticks in the smartphone app to maneuver the aircraft.

Up in the Air

Of course, the ultimate test of any aircraft is how it flies and, setting aside the collision avoidance system, it’s a middling performer and can be a little bit fussy. You cannot directly control the aircraft on take-off or landing. Instead, you push a button and wait while the Skydio 2 does its thing without any input from you.

Also, it requires a clear patch of ground to launch, or the flight control decision will overrule your command. I found this a bit annoying when I couldn’t get it to lift off in circumstances where I would be completely comfortable launching a DJI Mavic, Autel EVO or Parrot Anafi under my own control.

Finally, I would characterize the Skydio 2’s handling as sluggish. It is stable and it goes where you tell it, but it’s in no hurry to get there. While flying just a few feet off the ground, I found this bordered on being a safety hazard because I couldn’t move the drone out of danger quickly enough for my own comfort.

The app allows you to adjust the flight parameters, but this doesn’t seem to affect maneuverability all that much. Instead, the primary effect seems to be to raise the maximum speed from a pokey 10 miles per hour to a rather more brisk 30mph—although it takes its time getting there. Based on my experience, this is not an aircraft that you will ever fly strictly for the fun of it.

All that said, my declaration above about “setting aside the collision avoidance system” is not a fair criteria for judging the Skydio 2. It isn’t so much a drone with an integrated collision avoidance system as it is a collision avoidance system with an integrated drone. Dodging obstacles is what this aircraft was built to do—and seeing it in action borders on magic. Everything you have seen in the company’s promotional videos, and more, is completely true.

I would argue that the Skydio 2 is more capable than a human pilot in many of the applications for which it was designed. An example: flying through a stand of trees while the drone not only follows, but orbits, a moving subject. To pull off this maneuver, which the Skydio 2 manages with seeming ease, a human pilot would need to keep one eye trained on the video downlink, to keep the subject in frame, while the other eye tracked the drone itself and plotted a safe course while moving laterally through the forest. Unless you are a chameleon with a savant-level ability to do complex geometric calculations in your head, do not try this at home.

Less is Less

The Skydio 2 app is perhaps my greatest single source of frustration with the platform, mainly because it seems intent on denying you information that, in some cases, I believe a responsible remote pilot really ought to know. Furthermore, the company seems to actually pride itself on this lack of information.

Its website describes the app with the phrase: “More camera. Less cockpit.” Indeed, it puts the video downlink and camera controls front and center while only providing a minimal amount of telemetry: airspeed, altitude, distance to home, and battery life remaining—that’s it. The aircraft has a dual-band GNSS receiver (GPS/GLONASS) on board, but you would never know from the app. It does not tell you how many satellites it has in view or when a position lock has been achieved. Furthermore, the app does not give you any insight into what the collision avoidance system is perceiving, which can make it difficult to trust in some circumstances. Every other drone with a collision avoidance system gives you an on-screen indication as to what it is “seeing,” which you can correlate with your own observations of the environment.

The Skydio 2’s system is amazing, but even the company admits it isn’t completely foolproof. For example, it can’t detect objects that are less than half an inch in diameter, such as power lines or bare tree limbs. It would be great—verging on necessary, I would argue—to superimpose the collision avoidance system’s rendering of the environment on the main camera’s view. That would make it much, much easier to evaluate your surroundings and exercise good judgment before committing to fully autonomous flight.

The app’s quirks don’t end there, either. The default setting is for the camera to start recording video every time you lift off. Not an unreasonable choice for a flying action camera, I suppose, when you want to make sure you never miss a shot. However, it is deeply frustrating that it returns to this default setting every time you go flying. In order to stop it, you need to remember to disable auto-record every single time you spin up the propellers.

The good news, I suppose, is that it is much easier to revise software than it is to revise hardware. Building a separate app for enterprise users or even allowing pilots to enable different functions and telemetry options in the existing app would go a long way toward helping the Skydio 2 achieve its full potential.

The Skydio 2 incorporates three full-color cameras on the top and bottom of the aircraft, each with a 200-degree field of view—providing the aircraft with a complete picture of its operating environment in three-dimensional space.

The Real World

When I first saw the Skydio 2 at the 2019 Commercial UAV Expo in Las Vegas, my first thought was not that I should take up luge to capture amazing action shots of myself sliding down the side of a mountain, but rather that this aircraft has tremendous potential in real-world, commercial applications.

While I was impressed with its collision avoidance capabilities, the biggest factor driving that perception was the fact it is built in the United States. There has been increasing concern over the past couple of years that drone manufacturers based in China—which account for virtually the entire small, civil UAS market in the US—may pose a threat to national security by sharing information gathered from their drones with the Chinese intelligence services.

It occurred to me that a small, civil UAS that is manufactured in the US and could be sold at a reasonable price would potentially be a game changer—both for the company that built it and for the domestic industry as a whole. Now, news has emerging that Skydio is benefiting from that potential.

In total, federal government entities including the Army, the Air Force and the Drug Enforcement Administration have placed orders totaling nearly $5 million with the company.

Whether or not it can meet the demand remains to be proven, however. The company, which is headquartered and has its manufacturing facility in the Bay Area, was already struggling to keep up with demand from consumers before its assembly line was shuttered by the coronavirus pandemic. Still, of all the problems a business can have, too many customers is not generally counted among the worst.

The Skydio 2’s distinctive over-under propeller design allows its six collision avoidance cameras an unobstructed view of the environment, while the three-axis gimbal keeps the main camera steady during aircraft maneuvers.

What We Like

+ Extraordinary autonomous collision avoidance capabilities

+ Camera captures vivid imagery with wide dynamic range

+ App uses augmented reality to define maneuvers

+ Low price for robust capabilities; made in the USA

Bottom Line

The Skydio 2 incorporates ground-breaking technology to achieve an extraordinary degree of autonomous capability—actively tracking a subject through an environment crowded with obstacles while completing maneuvers that would overwhelm human pilots. Add to that robust construction, a gorgeous camera gimbal and a surprisingly reasonable price point and it looks like a winner. However, it is constrained from achieving its full potential by a few hardware and software quirks, some of which follow from its singular focus on becoming the ultimate flying action camera, even at the expense of being a better general purpose drone.

Is This Even Legal?

It’s a fair question: is the type of operation implicit in the Skydio 2’s marquee application—capturing action sports while flying autonomously—legal under 14 CFR Part 107 or the recreational rules described in Section 44809? If the subject is also the pilot, I don’t see how the answer can be anything but “No.”

Both commercial and recreational rules require the pilot to maintain visual line of sight with the aircraft throughout the flight. However, if you’re bombing down a foot path on a mountain bike, that isn’t going to be possible: your attention will be focused entirely on the boulder coming up fast and whether or not hitting it will cause you to flip over and snap your neck.

This problem could be solved by having someone else actually serve as the remote pilot, supervising the drone while it autonomously follows the subject. While this approach would, in theory, satisfy the line-of-sight requirements, there are still two issues: this doesn’t appear to be what most people are actually doing; and, if the drone is following a mountain biker or a person running through the woods, the remote pilot is going to lose line of sight pretty quickly, anyway.

Presumably to mitigate the risks involved in this type of autonomous flight operation, Skydio puts tight altitude restrictions on the aircraft while it’s following people or vehicles on the ground—minimizing the hazard to other air traffic. Good on them for that, but no technological system is completely reliable and it doesn’t change the fact that these sorts of operations almost inevitably will run afoul of the visual-line-of-sight rule.

Both commercial operators and recreational pilots should beware. If something does go wrong, nobody from Skydio will be standing beside you during your hearing at the Federal Aviation Administration. You alone will be held to account for your choices.

Text & photos by Patrick Sherman