There has been a fundamental change in the relationship between drones and public safety, according to Charles Werner — and he would know. Having spent 45 years in the fire service, he retired as the fire chief for Charlottesville, Virginia, and went on to establish and lead DRONERESPONDERS, a global alliance of emergency-response agencies with more than 1,000 member organizations worldwide.

“Over the past couple of years, I’ve seen people come to a realization,” said Werner. “Drones are more than just toys. Once people see what they can do, it quickly becomes part of the normal response in an emergency. Then, when it isn’t available, people are asking, ‘Where’s the drone?’”

Charles Werner is the chief emeritus of the fire department in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the director of the DRONERESPONDERS network.

Along with this shift have come new approaches to how drones are deployed, and what sort of missions they are able to fulfill. As an example, Werner cites the development of multi-agency drone teams to better serve the entire community in the event of a major incident.

“In York County, Virginia, for example, there is a combined team that brings together people from both the fire service and law enforcement,” he said.

The advantage of this approach is that whenever either one is facing a serious emergency—such as a big structure fire or an active-shooter incident—the affected agency wants all of its responders on the front line. During a three-alarm blaze, for example, the fire chief wants every firefighter on a hose line to bring it under control. However, the burden on law enforcement during the same incident is much less, meaning there will likely be a police officer available to fly the drone.

“Also, by using a multi-agency approach, all of the participants save money on training and equipment,” Werner explained.

Another trend is for agencies to use new applications for drone technology once they start to gain operational experience with it.

“First, they are flying more missions than they originally anticipated,” said Werner. “That means they need more pilots. Also, they start thinking about new missions for these aircraft, and now they realize they need one with a powerful zoom lens, or the option to deliver a payload, like a flotation device—and the small aircraft they started with doesn’t have all those capabilities, so they start looking at larger platforms.”

One trend that hasn’t changed is for drone operations to be assigned to existing personnel as a collateral duty: that is, someone already employed by the agency as a firefighter or police officer will be trained to operate the drone—rather than hiring a qualified pilot from outside the organization.

Growing Fast

DRONERESPONDERS launched in April 2019 and has been growing rapidly ever since: adding about 75 new members each week. One thing that has surprised Werner has been the growth in international membership.

“When we were looking to start the organization, we debated whether or not to aim for a worldwide audience, or just focus on the United States,” he said. “We finally settled on focusing our efforts domestically (and) because the rules about drones are different between different countries, we didn’t think we’d be able to keep up.”

In spite of that fact, nearly 20 percent of the organization’s membership is international, representing 55 countries around the globe.

“What has been really rewarding for me is that every time I check our website, we have 10 to 13 people online, and they are coming from everywhere: every state, but also South America, Puerto Rico, Ireland, London, Australia, New Zealand,” Warner said. “People are coming from all over the world to utilize the resources that we have online.”

In his view, one of the organization’s biggest assets is its membership map, which allows first responders to identify other agencies in their local area that are using drones, opening up the possibility for learning, partnerships and mutual-aid agreements. The map is available for free on the organization’s website (droneresponders.org).

“You can become a member through our website, too,” said Werner. “It only takes about three minutes to get signed up.”

Another benefit DRONERESPONDERS provides for its members, and the entire public safety community, is an annual survey that explores the use of drones by emergency response agencies.

“We’re trying to find out what the state of public safety is: What are the trends that are happening out there. We also wanted to know things that would be of interest to our corporate patrons: What are their budgets? What new aircraft are they planning to buy?”

The Results Are In

About 600 agencies responded to the organization’s 2021 survey. Before considering the results, it is important to recognize how this poll was conducted: DRONERESPONDERS sent the survey to each of its members, as well as non-member organizations through their profiles on social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

This is what social scientists refer to as a “convenience sample,” which is data gathered from a group that was easy to contact but not necessarily representative of the overall population. If an agency is a member of DRONERESPONDERS, or follows the topic on social media, is it more likely to have a drone program or at least be considering whether to start one? You betcha!

Convenience sampling does not offer the same rigor or repeatability of a randomly selected sample of the population as a whole, but nevertheless it can provide some useful insights. For one, it appears that DJI continues to dominate its rivals in selling drones for public safety applications, with 90 percent of the respondents reporting they owned one or more aircraft from the Chinese manufacturer.

“We did see one interesting change from last year’s survey,” said Werner. “Last year, Skydio was the No. 2 manufacturer, but this year Autel Robotics took over that position.”

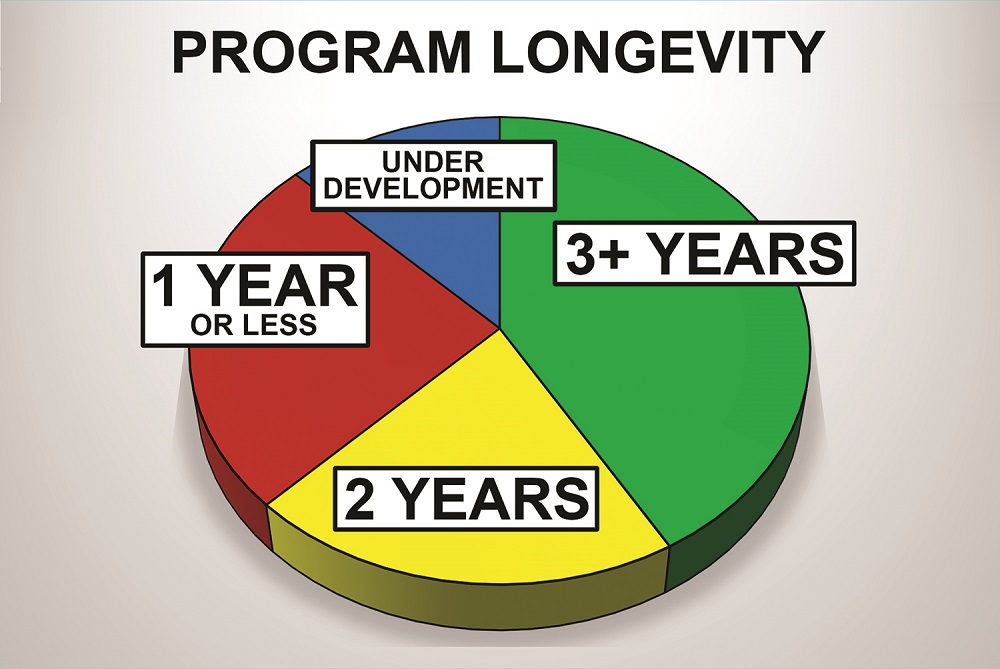

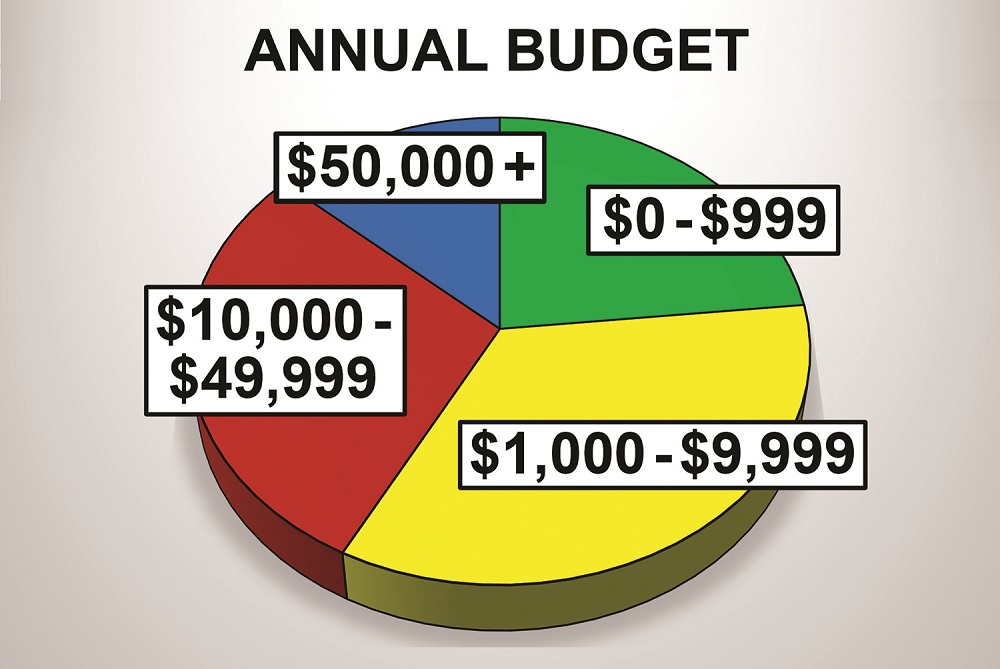

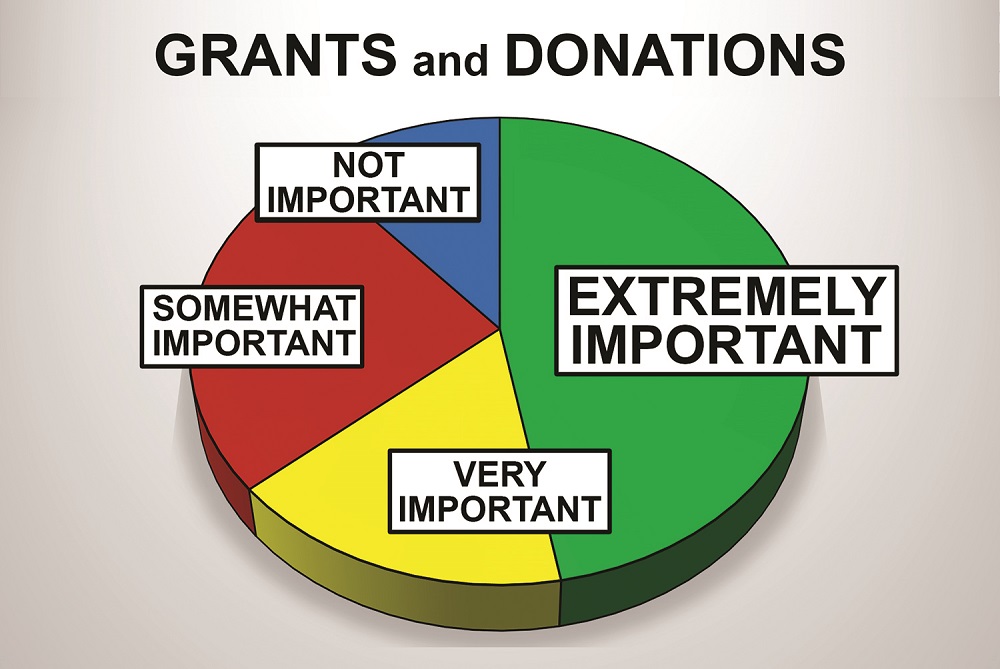

Other key findings include the fact that of agencies with drone programs, less than half have been active for more than three years. Also, more than half of the agencies that responded to the survey have an annual budget for their drone program that is less than $10,000 per year—and grants and donations represent a critical source of funding for those programs.

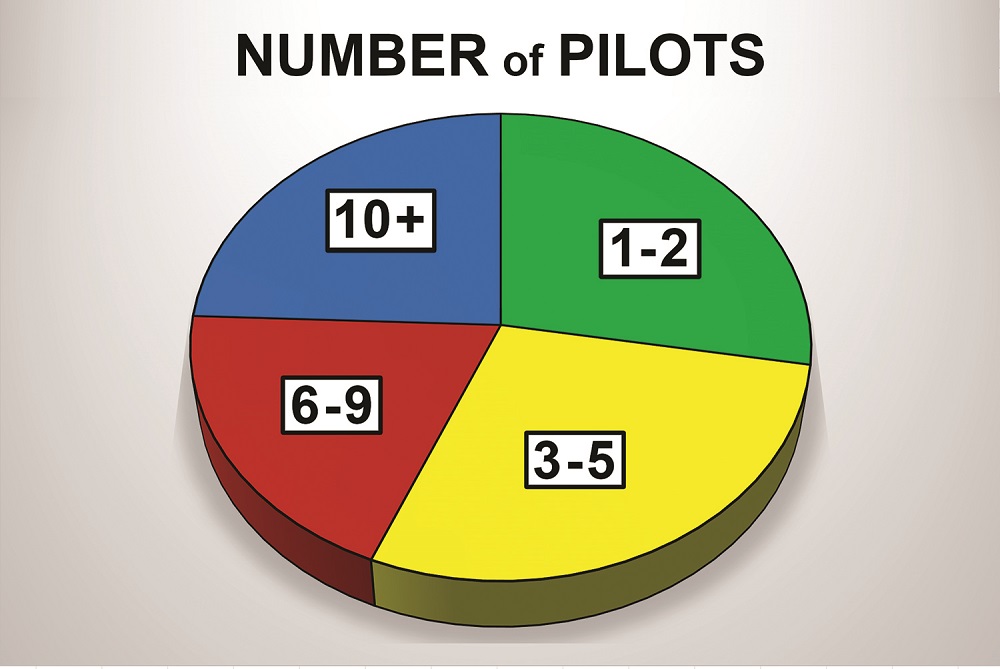

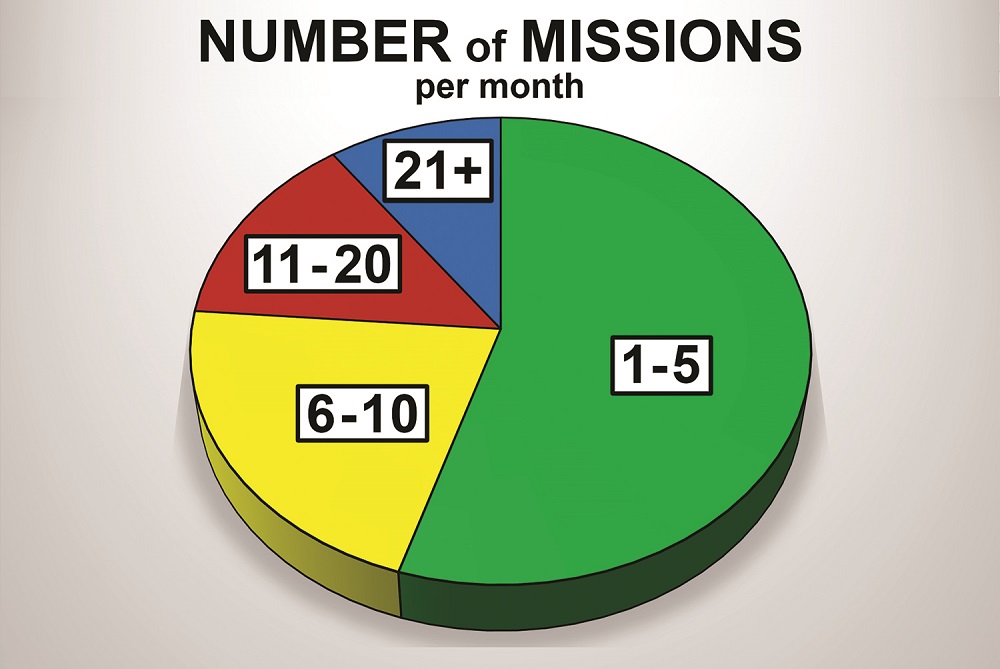

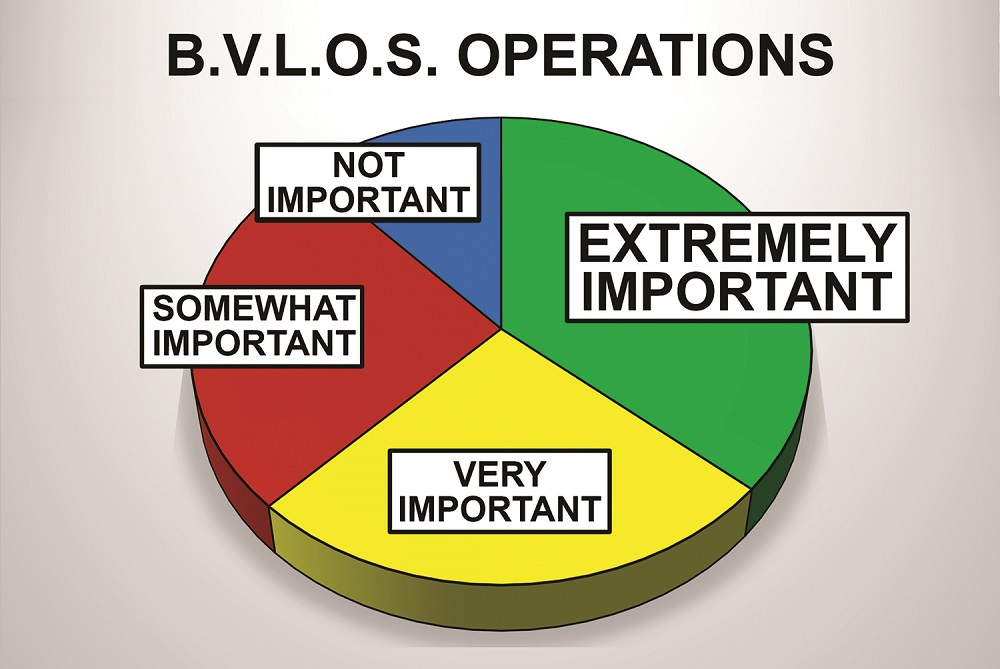

The majority of agencies have fewer than five pilots on staff and fly less than six missions a month, including training missions. About two-thirds of responses came from agencies that ranked the ability to fly beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) as either extremely important or very important for their program to achieve its full potential.

The Future

In short, the use of drones in public safety is still in its early stages, but it is growing rapidly, and the leaders in this effort are beginning to make changes to the structure of their organization to take the maximum advantage of the possibilities offered by this new technology.

“We are beginning to see agencies where they are literally flying every day,” said Werner. “For example, FDNY is going to full-time staffing for its drone units. Chula Vista, California, is also employing full-time pilots as part of their program.”

He sees autonomous operations, drone swarms and BVLOS as being the next big steps forward for the use of drones by firefighters and police.

“Another part of that is going to be artificial intelligence to analyze the data coming from them,” said Werner. “I’m working with NASA, and they are looking at doing something for disaster assessment—comparing satellite imagery from before the event with drone imagery gathered afterward. In our study, we saw 17 major use cases that were identified, and those are divided into three categories: pre-incident, during the incident and post-incident.”

He also believes that the reliance on pilots with nimble thumbs to control the aircraft in real time is likely to wane as the technology continues to develop. “One thing I saw recently that made me think that is a company out of Israel called Highlander: you decide where you want the drone to do and you just push a button,” Werner said. “Then, as the flight continues and its battery runs down, another drone is launched automatically to take its place before the first one returns to home, so you’ve got continuous coverage over an incident.

“You can still take direct control if you want to, but I think that will go the way of manual transmissions in cars: It’s just easier to use an autonomous system except in a few, specialized applications.”

Werner believes that in the next five to seven years, 90 percent of public safety agencies will have a drone program. He added, “I think that’s the evolution that’s happening—and it’s happening pretty fast.”

BY PATRICK SHERMAN

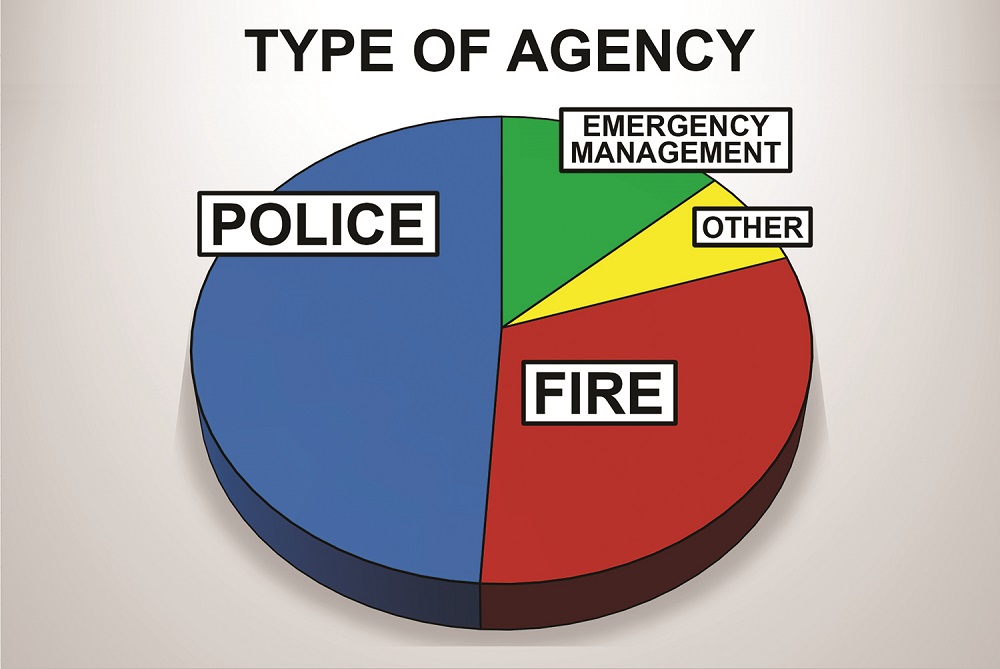

Nearly half of the agencies surveyed by DRONERESPONDERS in 2021 are law enforcement. Their ability to seize forfeited assets—cash and even drones—can be an important advantage when starting a new program.

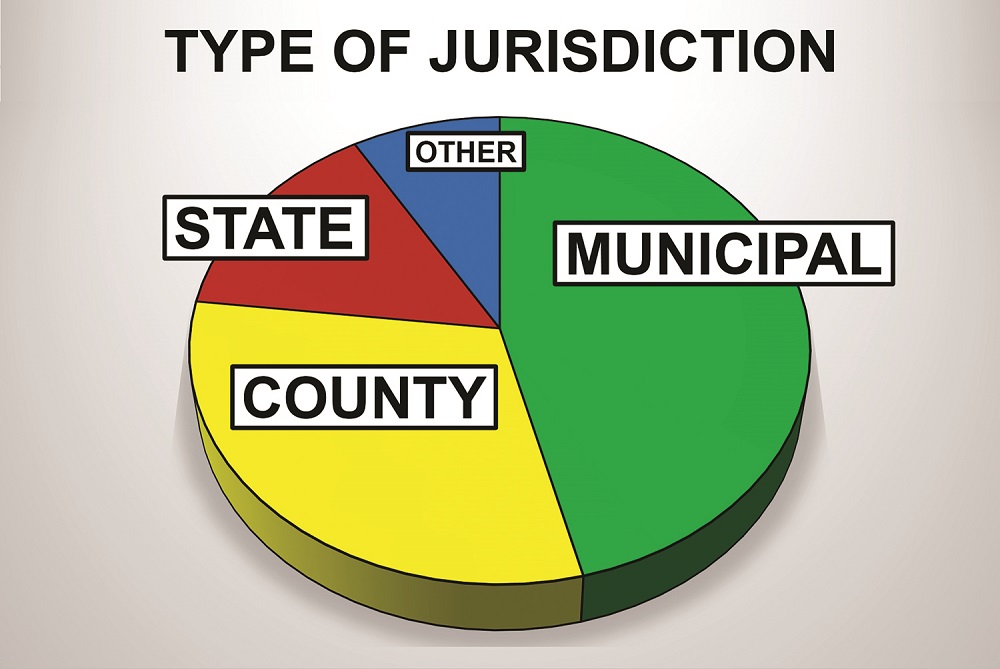

Of all the public safety agencies surveyed, the overwhelming majority belong to a local branch of government such as a county or city.

More than half of the public safety agencies that answered the DRONERESPONDERS poll have had a drone program for less than three years or are still considering developing one.

A majority of public safety agencies with a drone program have an annual budget of less than $10,000 to support their operations, including the acquisition of new aircraft, according to the DRONERESPONERS poll.

The use of different types of sensors on board drones, such as thermal-imaging cameras, can provide firefighters and other first-responders with a valuable perspective of what is happening on the ground in an emergency.

According to the DRONERESPONDERS survey, grants and donations are an essential source of funding for drone programs nationwide.

While it is still in the early days for drone programs across the public safety community, nearly a quarter of agencies that answered the DRONERESPONDERS survey indicated that they have 10 or more pilots in their organizations.

More than a half of agencies that provided feedback for the DRONERESPONDERS survey indicated that they fly between one and five missions per month, including training missions.

The results of the DRONERESPONDERS survey indicate a strong demand for the ability to operate drones beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) to support public safety operations.