Expert keys to a successful small business

As the demand for the unique capabilities of drones soars ever higher, even as the advances in drone tech lower the barriers to meeting those demands, the chance for pilots to turn their skills and enthusiasm for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) into business opportunities is exploding. But with those opportunities come their own set of challenges. We’ve all heard about the Section 333 Exemption process from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for commercial drone operation, and recently, the FAA has been making more ripples in the UAV community with mandatory drone registration for all pilots. And looming on the horizon is a proposed set of new FAA regulations known as “Part 107” which might (or might not) replace some (or all) of the 333 Exemption rules. To pilots looking to turn their hobby into a way to make a little extra cash on the side or even start their own small business, the maze of regulations can be utterly bewildering. You are probably asking yourself important questions such as “Which rules apply to me?” or “Do I need a Section 333 Exemption?” and “How do I apply for one?” We turned to three experts to help us decode the mysteries of commercial UAV regulations, to aid drone pilots like you in taking that next step toward earning some income doing what you love! Here’s what they had to say.

| WE ASKED THE EXPERTS We put a variety of questions related to small-business drone operations—and the FAA requirements for such—to these three men. Each comes at the subject from a different angle, but all provided a wealth of knowledge and valuable perspective on the commercial-drone market as well as the logistical and legal aspects of stepping up from being a private UAV pilot to for-profit flying. |

Gus Calderon Founder of AirSpace Consulting, FAA-certified commercial pilot, commercial drone pilot and instructor, and professional consultant for filing FAA Section 333 Exemptions |

John D. Deans Owner/proprietor of Central Texas Drones, FAA-certified private pilot, drone pilot, and author of the new book Become a U.S. Commercial |

Jeffrey Antonelli Founder and lead attorney at Antonelli Law, Ltd. (member of the DJI Professional User Referral Program), leader of the firm’s Drone/UAS Practice Group, member of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), and FAA Section 333 legal consultant |

The Market

RotorDrone: What types of industries/businesses hire individual pilots on a contract basis? Are certain ones more lucrative or have a higher demand?

John Deans: Real estate, construction, surveying, oil and gas, agriculture, law enforcement, fire and EMS [emergency medical services], and power companies. Real estate is the easiest and most lucrative right now, followed by construction. Agriculture along with oil/gas pipelines will follow soon.

Gus Calderon: Over 50 percent of my clients are doing aerial filming for production companies. I also have clients using their exemptions for mapping, real estate, power-line inspections, surveying, advertising, and land-use planning.

RD: Are certain industries better suited to pilots of a certain experience level (i.e., novice versus veteran)?

JD: The current FAA 333 Exemption requirement of having at least a Sport Pilot’s license greatly enhances the skill level and aeronautical awareness abilities of the UAV pilot. Simply purchasing a drone and trying to be a commercial UAV pilot is a no-go.

RD: Do you have any specific recommendations in terms of specialized skills (beyond basic piloting competence) that an aspiring pilot should have to be more successful/marketable?

JD: Number one, you have to be a successful small-business person with good marketing skills. And you will need both the photography and videography skills along with the editing and post-processing equipment, software, and talent.

RD: Should beginners consider working for free to gain experience—and if they do, do they still need a commercial (333) exemption from the FAA?

JD: I strongly recommend pilots perform pro-bono flights before you file for the 333 Exemption.

RD: Will opportunities expand for individual/part-time pilots, or will the industry become more “professionalized”?

JD: Initially, for the next couple of years, we are the pioneers as independent commercial UAV pilots. By 2020, the drone-service insourcing will begin to bring costs down, risks lowered, and corporate standards established. Right now is the UAV Wild West—and I’m loving it!

Energy industry operations, like oil/gas pipeline inspections, are among the opportunities on the rise for pilots looking to earn money doing what they love.

Flight operations in urban areas or with people nearby will likely involve municipal permits, liability waivers, and various other local legal requirements beyond those covered by an FAA Section 333 exemption. For this reason, it is often advisable to enlist a law firm and a technical consultant like our experts to make sure that you are covering all the bases.

The Law

RD: Why is obtaining a 333 Exemption important if pilots are looking to use a drone to earn money? What are the consequences/penalties if they don’t

have one?

Jeffrey Antonelli: There are generally three types of negative consequences for operating commercially without a Section 333 Exemption: FAA penalties, insurance availability, and hindering the ability to

market oneself.

› FAA. While the FAA’s position that model aircraft and drones are “aircraft” is controversial, operating without a Section 333 Exemption raises the possibility of being prosecuted by the FAA for violations of the FARs (Federal Aviation Regulations). The could mean anything from having an educational encounter with no penalty up to many penalties for violating the many FARs (not having an airworthiness certificate or minimum amounts of fuel onboard, for example), which could mean fines of $1,000 to much more. The case against SkyPan International made the news when the FAA proposed a $1.9 million fine for unauthorized operations, including alleged flights in New York’s Class B airspace. As of the date of this writing, the FAA has opened at least 24 cases and has settled 12.

› Insurance. Many aviation carriers will not issue insurance coverage for operations that do not have a Section 333 Exemption.

› Marketing. An increasing number of businesses will not hire a drone operator without a 333 Exemption. We first saw this in the cinematography field, but the requirement of having a 333 has now gone much wider. In addition, having a Section 333 Exemption means the business can “come out from the shadows” and put themselves out in the public eye without worrying about possible FAA enforcement action. Many operators flying without the Section 333 Exemption must rely on word of mouth and repeat customers.

RD: People can file for an exemption themselves individually, or there are many law firms and consultants out there who will assist

them. If pilots file individually, what is involved in terms of paperwork and fees?

GC: The amount of paperwork required depends on whether the petitioner is filing an exemption for aerial data collection or closed-set filming. The request to conduct closed-set filming operations is much more complicated because, if granted, it will allow the petitioner to conduct UAS [unmanned aircraft system] operations within close proximity to people in a controlled environment. This type of operation requires the submission of a Motion Picture and Television Operations Manual (MPTOM), which is beyond the scope of most people to write. Even with my experience as an FAA-certified air-charter operator, it took me about 200 hours of research to write an MPTOM.

JA: Paperwork includes the petition for exemption itself, an operations manual, and possibly additional manuals such as training manuals and the MPTOM if requesting closed-set filming. Doing it oneself without assistance can be done, but to do so correctly will take time to make the petition and operations manual conform to the actual operations. Reports vary from several hours to a number of months, particularly for larger commercial operations. There are no FAA filing fees currently.

RD: Are there things people should or should not do that will impact their chances of being approved?

JA: Be sure to address all the relevant FARs you wish to be exempted from, and do not forget to include a statement of public interest; that is why the petition being granted would benefit the public as a whole. See the FAA’s website (aes.faa.gov/petition/index.html). Finally, provide the reasons why the exemption would not adversely affect safety or how it would provide a level of safety at least equal to that provided by the rule from which you seek an exemption.

GC: It is imperative to monitor the public docket once it is opened, because if an incomplete petition was submitted, the

FAA will send a “Request for More Information” (RFMI) and that will require a response within a specified deadline. If the FAA does not receive the missing information within that time, they will close the docket and the petitioner will have to start from

the beginning.

RD: If someone hires a consultant or law firm to help them file, what are the advantages and disadvantages?

JA: The advantages of hiring a law firm to file the Section 333 petition are (1) save time, (2) knowing the petition is done correctly, and (3) establishing a relationship with a drone lawyer that can help you with your business needs, interpret the ever-changing FAA policies on drones, and, if necessary, defend against any FAA actions. When people hire my own law firm, we also include the required FAA commercial UAS registration, which can be a frustrating task for many people. Finally, lawyers have fiduciary duties to their clients that other service providers do not have.

GC: The Section 333 exemption process requires an understanding of aviation language and regulations, which most people do not have. While there are people who do navigate the process successfully on their own, many others have problems that cause them costly delays. The first six exempt companies had an attorney prepare the petition and a consultant write the operating manuals, and this is clearly the most advisable route to choose. I work with several aviation attorneys, and they not only provide legal advice but they often help the client form business entities such as an LLC or Corporation. As a consultant, I prepare operating manuals and educate the client about compliance and record-keeping requirements required under an exemption.

RD: What does a firm typically charge?

JA: While it depends on the complexity, as part of the DJI Professional User Referral Program, our firm charges $1,250 for most Section

333s, which also includes up to two FAA commercial UAS registrations. Certain restrictions apply, including that you must use at least one

DJI airframe/RTF drone. Without a DJI airframe/RTF drone the price

for most 333s is $1,500, with some uses bringing the fee up to

$7,500 or more.

RD: Does professional help substantially impact the approval rate?

JA: Professional help can certainly reduce the likelihood of delay from the FAA needing additional information. Even highly experienced pilots hire us because the paperwork burden is too high.

RD: What sorts of things should people look for when selecting a firm to help them with their application?

GC: When selecting a firm specializing in Section 333 exemptions, be sure they have an extensive aviation background. As a commercial pilot with over 20 years of aviation experience, it has taken me years to understand the Federal Aviation Regulations. Also, the Section 333 exemption process is constantly evolving, so if you do seek assistance, I recommend using a company that has been in the business over one year.

If you are considering hiring someone to help you, ask about the requirements to actually operate after receiving an exemption. Unfortunately, many people are so focused on receiving an exemption, they do not realize they do not meet the requirements to actually use it! For example, many people still do not realize that the pilot in command of a commercial UAS must hold an FAA pilot’s certificate. Additionally, conducting UAS operations within close proximity to consenting personnel involves increased liability risk. Anyone thinking about this type of exemption should seek the advice of an attorney.

RD: How long does it usually take for the FAA to approve a 333 Exemption?

GC: The FAA states on their website that the Section 333 exemption process takes between 90 and 120 days. What most people do not understand is that the “clock does not begin ticking” until the FAA opens their public docket. At this time, it takes approximately 60 days until public dockets are opened because of the overwhelming number of petitions that are being submitted. To be realistic, one should anticipate receiving an exemption in approximately six months from submitting their petition, assuming their request has been properly prepared.

RD: Do you know what the approval/rejection rate is?

JA: The rejection rate has been around 10 percent. The latest figure from FAA is 399 rejections out of 3,528 submissions (11 percent) as of

January 20, 2016.

RD: Is there anything a 333 Exemption does not cover that a small-business operator might encounter?

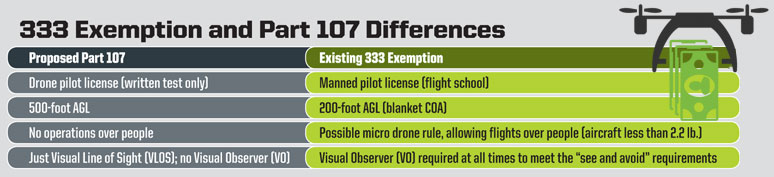

JA: Yes. Flights above 200 feet AGL [above ground level] and flights within five miles of airports are not allowed. The “blanket” COA [Certificate of Authorization] everyone gets with their Section 333 approval only allows flights up to 200 feet AGL. If you need to go higher, such as for precision ag or tower inspections, you will need a special COA. Finally, no Section 333 Exemptions have allowed flights over people who were not participants and essential to the flight operation.

RD: Will 333 Exemptions be superseded or nullified by Part 107? And if so, should small operators consider waiting until those rules are official, or is it still worthwhile to obtain an exemption?

JA: We expect those who have a Section 333 Exemption to get the benefit of its permissions to the extent that the actual Part 107 when it comes out may be more restrictive. However, Part 107 when it comes out may be very different than the NPRM [Notice of Proposed Rulemaking] that came out in proposed form last February. Until it comes out, nobody can say for sure what it will look like.

GC: I have been told by senior FAA officials in the UAS Integration Office that “The exemption process is never completely going away.” The “summary grant” exemptions, which most have, will be superseded by Part 107 regulations. The FAA issues a summary grant when it finds it has already granted a previous exemption similar to the new request. Those operators who were granted privileges beyond the scope of a summary grant exemption (such as drones over 55 pounds, beyond visual line of sight, flight instruction, etc.) will continue to use the exemption process. Most people outside of aviation don’t realize that the exemption process has existed for decades. Operators and manufacturers have used the exemption process when a certain regulation is burdensome and they can prove an equivalent level of safety exists.

RD: Do we have a sense when those rules will be announced?

GC: I have heard from senior FAA officials in the UAS Integration Office that Part 107 will be in effect by August of this year. Keep in mind that exemptions are only valid for two years, and the first ones were granted on September 25, 2014. Those operators would need to request and receive an extension prior to that date in order for them to continue operating under their exemption if Part 107 is not in place.

JA: Nobody knows. Speculation from “insiders” has ranged from springtime to possibly several more years. If you are tired of waiting and want to be legal now, do a Section 333. If you can continue to wait for an uncertain length of time, I would say maybe wait to see if Part 107 gets published by June of 2016 and see how long FAA says it will be until you can actually go take the written test for the new drone pilot license.

Aerial cinematography—like that used in the filming of this PBS documentary shot at the Gettysburg National Military Park—can provide lucrative and exciting opportunities for UAV pilots. But these can be among the most complex flight operations to conduct, requiring a Motion Picture and Television Operations Manual (MPTOM) outlining all safety procedures undertaken. helicopter camera flying over Gettysburg National Battlefield. Boritt is filming “The Gettysburg Story” documentary to be broadcast on public television in Spring 2013.

Bottom Line

After grilling our experts on as many aspects of commercial-drone use as we could think of, we’ve confirmed that it is still a complex and ever-changing landscape. That presents exciting opportunities and significant challenges for pilots aspiring to take their passion into the realm of for-profit flying. Ambitious and organized pilots can go it alone—particularly if they have resources like John Deans’s book at their disposal—but after speaking with our experts, we feel that professional help is a worthwhile choice for most people aspiring to start a drone-related small business. The opportunities are out there, and they’re expanding every day. Be smart, be organized, educate yourself about the rules, and go out there and get paid to fly!

By Matt Boyd