If you have ever listened to crewed aircraft pilots communicating with one another or with air traffic control, much of the conversation may sound almost like a foreign language. Alpha bravo this, midfield downwind that. Niner? Like a forty-niner? What does all this mumbo-jumbo mean? You may be thinking: “Who cares? I’m not a crewed aircraft pilot.” That may be true for many of you, but the fact is that you can glean a lot of information about aircraft activity in your vicinity, especially if you are operating (with permission) in areas nearby manned aircraft. Your situational awareness—the knowledge of what all is going on around yourself—can be greatly enhanced by monitoring aviation radio frequencies in use at nearby airports and other facilities. In fact, it is often advocated that drone pilots carry an aviation radio with them for this purpose. I’d even argue it should be a required piece of equipment, but as of right now, it’s not mandated as such. So perhaps now you’re thinking, “Hey, that actually sounds like a good idea, but where do I start?” Well, let’s dive in and see how aviation radio communication works and how to decipher the common language and terms used on the airwaves.

First a caveat, though. While listening to aviation radio frequencies is a great idea, transmitting (i.e., talking) on them is a no-no unless you are properly licensed to do so. So you might be tempted to go out and buy a fancy transceiver (a radio that can transmit and receive) or try out your skills at aviation lingo outlined here, but think again. The Federal Communication Commission (FCC) regulates all this stuff, and they don’t want just anyone jamming up aircraft radio communications willy-nilly. Unless you are a certificated manned aircraft pilot, you will need a stand-alone radio operator’s license. It’s not hard to get, but you will want to do so prior to pushing transmit. Interestingly, the operator’s permit granted to manned aircraft pilots is only good in the U.S., and pilots also need a special permit to transmit outside U.S. borders.

RADIO FREQUENCIES

Aviation communications take place using very high-frequency (VHF) waves similar to FM radio. Aviation uses the spectrum from 118 to 137 MHz, just above FM (which uses 88 to 108 MHz). Certain frequency arrangements are commonly used for specific purposes, though this can always vary. For example, frequencies from 121.60 to 121.90 MHZ are typically reserved for use on the ground at airports with a control tower (also referred to as “ground control”). Frequencies from 122.00 to 122.95 typically are used for weather discussions with Flight Service Stations (which pilots will call “radio”). One frequency pilots of every type should know is 121.50, which is reserved for emergencies (so you definitely want to avoid talking on this one).

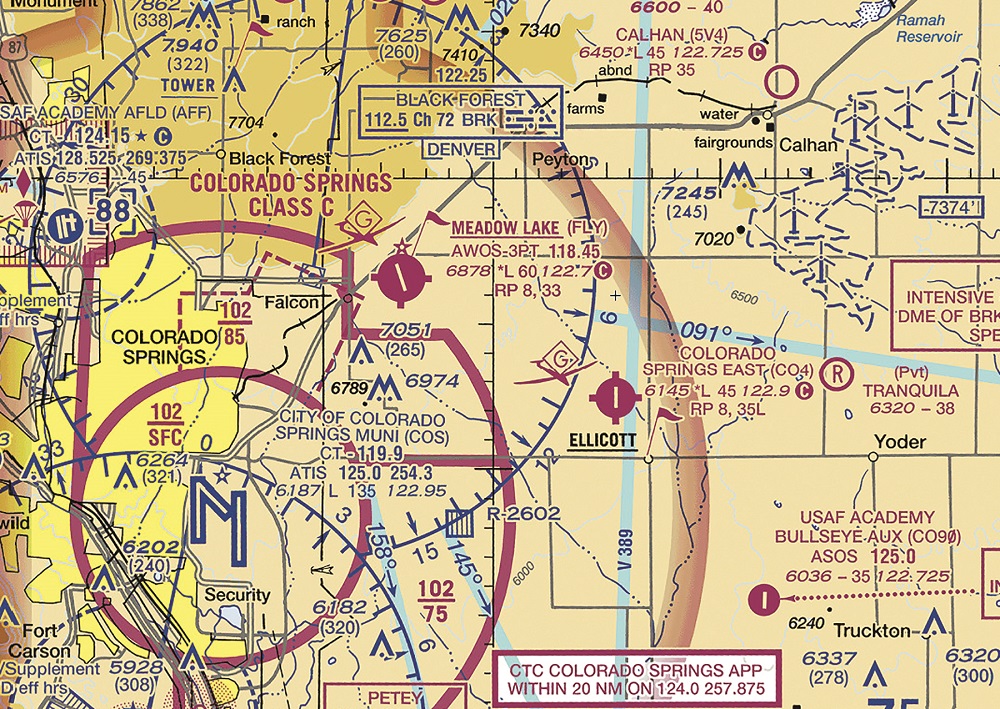

To figure out what frequency or frequencies you may want to listen to, refer to your local aviation sectional chart (see the June/July and August/September issues of RotorDrone Pro for more information on how to read them). A great place to find your local map is on skyvector.com. Another place to look is the FAA’s Airport/Facility Directory (AFD), though some knowledge on how to decipher its contents is required (on faa.gov, search “chart supplements”). The best place to start is to look for airports near where you are going to fly. Most portable radios have the ability to monitor several frequencies, continuously scanning through what you have set. Let’s take a look at an example in the Colorado Springs area to see what I mean.

COLORADO SPRINGS EXAMPLE

Let’s assume you’re inspecting some wind turbines (those windmill symbols in the upper right corner of the sectional excerpt in Figure 1). There are a handful of public airports (private ones are those with “R” in a circle and usually aren’t used much) in and around the area. Calhan airport is the closest, while Colorado Springs East is just over five miles away. Other proximate airports are Meadow Lake, USAF Academy Bullseye Auxiliary, and the largest, the City of Colorado Springs Municipal. Looking at these airports, note the number adjacent to the letter “C” within a shaded circle. For Calhan, this is 122.725, the MHz frequency for the common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) for the airport. The CTAF is the frequency most commonly used by aircraft to broadcast their intentions at airports without a control tower (or when the tower is closed). Thus we’d want to program in the CTAFs for adjacent airports. Other frequencies we may want to include at the control tower (CT) at local airports, such as at Colorado Springs on 119.90 MHz. At big airports like Colorado Springs, there may be additional frequencies to handle inbound and outbound aircraft. In this case, note at the bottom of Figure 1 there is a white box with a frequency of 124.00 for Colorado Springs Approach Control. This might be one to add to one’s radio for good measure.

The next tidbit of knowledge that is applicable to mention here is how aircraft normally operate in and around airports. Small planes that are arriving or departing an airport usually will fly higher than 1,000 feet above the ground when beyond a few miles from the field. If an aircraft is remaining nearby the airport, say to practice takeoffs and landings (which is referred to as “staying in the pattern”), they will operate at traffic pattern altitude, which usually is from 800 to 1,000 feet above the ground (the exact value can be found in the AFD). Larger aircraft will commonly stay high until coming in to land, only descending below 1,000 feet when within three or four miles of the airport. They will typically climb out rapidly after lifting off the runway. Long story short, unless you’re operating right near an airport, you should not usually be anywhere near a manned aircraft as you’ll most likely be below 400 feet above the ground anyway. Most likely, the only type of aircraft you may see that low is a helicopter. Unfortunately, most heliports are not marked on sectionals, and, among those that are, they do not always have frequencies associated with them and/or pilots rarely use them. Beware that you may also get the occasional helicopter coming or going from any type of airport.

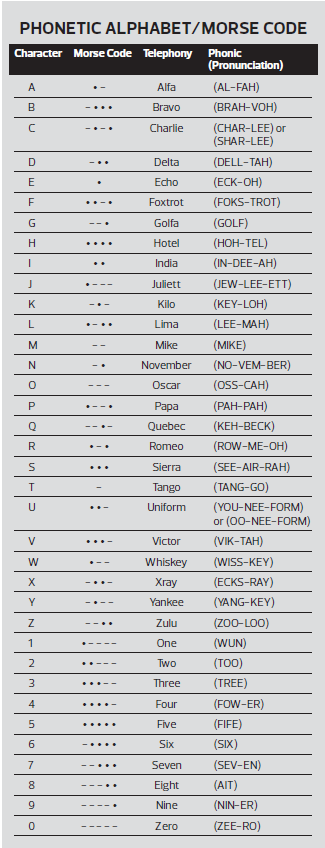

Ok, so you have figured out what frequencies to listen to, but what is all the jargon being thrown around even mean? You will want to know how to decipher a few basic things when listening to pilots and controllers talk. Starting with the most basic is the phonetic alphabet. In order to avoid confusion about what letters radio users intend to convey, words are used instead of simply saying “B” or “C” because they could potentially be confused. The key to the phonetic alphabet can be found in the Aeronautical Information Manual Chapter 4-2-7 (available at faa.gov) and in the sidebar in this article.

Instead, you would use “Bravo” for “B” and “Charlie” for “C.” Numbers are also presented in specific, unique ways. For example, the number nine is referred to instead as “niner” so to avoid confusion with the German word “nein,” which means “no.” Three is “tree” and five is “fife” again to avoid any ambiguity. Weird, yes, but true. Usually, numbers are stated individually. For instance, a pilot announcing intentions to land on runway 36 would say “three six” not “thirty six.” But when announcing their altitude, pilots will use thousands and hundreds as descriptors, such as 1,500 being “one thousand, fife hundred” and 800 being “eight hundred.”

Another thing to know is that aircraft have names, referred to as “call signs.” For non-commercial aircraft, this will be their registration number, i.e., the numbers and letters you see printed on the side of the plane. Aircraft registered in the U.S. begin with the letter “N,” which will be announced “November” while those from Canada are denoted by “Charlie” for “C.” This first letter is then followed by a registration number or letter/number combination up to five characters long. One of my favorite airplanes growing up was N6115Q—“November six one one five Quebec.” This is what we used to announce who we were and where we were going. Usually, the aircraft manufacturer is substituted for “November” for communications in the U.S. Also, once an aircraft has initially announced itself on frequency, its call sign is shortened for simplicity using the last three characters only. Thus N6115Q, a Cessna 152, becomes “Cessna one five Quebec.”

AIRPORT OPERATIONS

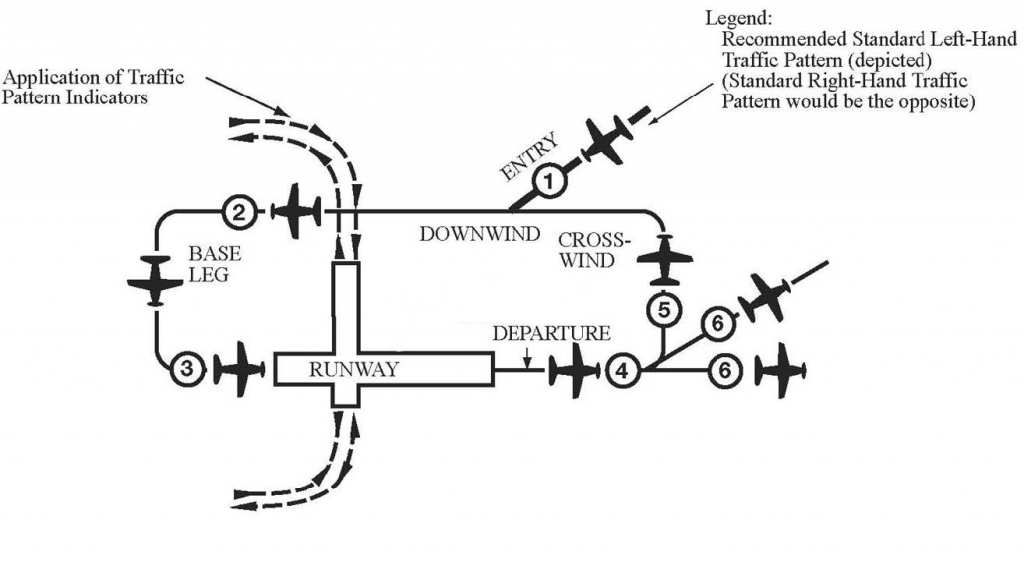

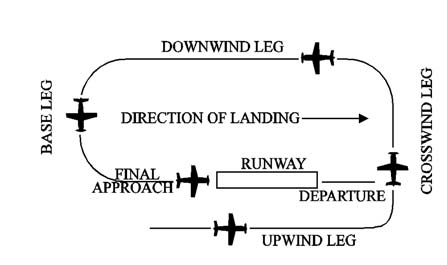

Now let’s dive into how aircraft typically operate around airports. Aircraft approach airports to enter the “traffic pattern” so as to maneuver to align with the desired runway for landing. Pilots prefer to land into the wind; thus, they will normally pick the runway best facing into the wind direction. Runways are numbered based on the direction they are heading in relation to magnetic north (what would be read on a compass). For example, runway 36 is aligned with a 360 or due north heading, while runway 9 is aligned with east, or 090 degrees. Traffic patterns are divided up into five legs (see Figure 2). Departing aircraft fly the “upwind” leg, which is aligned with the departure end of the runway. The left perpendicular to the departure end is referred to as the “crosswind” leg. The leg parallel to and towards the landing end is called the “downwind” leg, because you’re usually flying downwind on it. The leg perpendicular to the landing end of the runway is called “base,” and when aligned with the runway for landing, aircraft are on “final approach.” Traffic patterns are typically set up so that all turns are to the left, but in some cases, they are to the right, for example, to avoid buildings, reduce noise impacts, and so forth. Airports with right-hand traffic patterns will depict such on sectional charts by denoting “RP” and the runway number associated with the non-standard pattern. Looking back at Figure 1, Calhan airport uses a right turn traffic pattern for runway 35.

Aircraft are supposed to approach an airport at a 45-degree intercept to join the downwind leg at a point aligned with the runway’s midpoint at traffic pattern altitude (see Figure 3). They will then turn downwind and continue in the pattern for landing, only descending from pattern altitude when approximately abeam the landing end of the runway. They will typically only get down to 400 feet or below when within about a mile of the runway end. Aircraft will ordinarily be at 200 feet at a point approximately half a mile from the runway. Departing aircraft have more options open to them: they will depart the traffic pattern straight out (upwind), at a 45-degree angle between upwind and crosswind, or even heading downwind. Do note that pilots can do whatever they want at airports with no control tower, so they may be creative in arriving or departing the area. For airports with control towers, air traffic control will dictate how pilots maneuver in the vicinity.

Some other helpful things you might hear on aviation radio frequencies are information about aircraft position and weather conditions. At airports without control towers, pilots will often report as they approach or depart an airport in terms of the direction they are from the airport and how far and what they intend to do next. When there is a control tower, things will be much more organized, with detailed position and distance information being the norm. Weather details, such as wind, temperature, barometric pressure, visibility, cloud heights, and cloud cover, are commonly discussed. Weather and other airport information is also available through an automated recording at busier airports on ATIS (Automatic Terminal Information Service) frequency, which is marked as such on sectional charts. A few things to keep in mind: wind is reported in terms of the direction it is blowing from, and its strength is noted in knots (nautical miles per hour). Thus winds reported as “two two zero at one four” means the wind is blowing from 220 degrees (out of the south-southwest) at 14 knots. Temperature is in Celsius, barometric pressure in inches of mercury, visibility in statute miles, cloud heights in feet, and cloud cover is described as scattered, broken, overcast, obscured, or clear.

AN OVERVIEW

Let’s now put it all together for some practical use with an example of what you might hear if eavesdropping on aircraft in the local area, as shown in Figure 1. Tuning into Calhan’s frequency of 122.725, we hear an aircraft call “Calhan Traffic, Piper one eight four one lima, entering a forty-five-degree entry for runway one seven, descending out of eight thousand, Calhan Traffic” (note: pilots often use nonstandard language, so let commonsense fill in the blanks as necessary). Where might this airplane be, and could it be a factor if we are currently inspecting the wind turbines? If you recall, unless otherwise noted, traffic patterns are made with turns to the left and runway 17 faces towards the south (170 degrees magnetic); therefore, an aircraft entering a 45-degree entry for the downwind leg would be east of the airport/runway, allowing for left turns to base and final approach. You will likely see the aircraft because it will be passing close to your position, depending on which turbine(s) you are currently inspecting and because the turbines have an elevation of around 7,374 feet (as noted to the right of the symbols on the sectional), the airplane’s altitude may be getting close to where you might be operating.

While this was a quick overview of aviation lingo and how to tune it in, the best way to learn about aviation speak is to listen regularly to air traffic communications. A great way to do this without a radio is via liveatc.net. You can ramp up your aviation communications knowledge immensely by tuning in along with your Chapter 4 of the AIM. Coupling this with visual observation or flight tracking apps/websites, you can learn a lot about how aircraft move in local areas, in and around airports, and so forth, along with how all of this is (or is not) communicated to air traffic control and other aircraft. By doing all of these recommendations while not operating your drone, you can be best prepared to use aviation radio transmissions for situational awareness when you do, in fact, have your drone in the air.