As a professional drone pilot, conquering the hours of darkness means acquiring new knowledge, thinking seriously about safety and clearing bureaucratic hurdles—but it opens up a whole new world that only a few have begun to explore.

According to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), there are 180,000 certified commercial drone operators in the United States, and waivers have been issued to 4,400 of them allowing for night time flights. Simple arithmetic reveals that this elite group constitutes 2.5 percent of the total population of drone pilots. If you’re not one of them, then each aircraft you own is really only half a drone, because you can only fly it for half of the year—the half when the sun is above the horizon.

Applying to the FAA for a certificate of waiver may seem like a daunting prospect. Everyone in the commercial operations community has heard horror stories of applications repeatedly rejected through an opaque bureaucratic process. It can seem like only the lucky, the supremely well-educated, those wealthy enough to hire specialist attorneys and people with connections are able to navigate the process successfully.

Earning the right to fly at night is a challenge, to be sure—but it isn’t impossible. Like filing your taxes or climbing Mt. Everest, the key to success is a systematic approach: begin by understanding the process, break it down into smaller steps that can be more easily accomplished and simply persevering. As in any other aspect of life, the percentage of successful outcomes achieved by people who never begin or give up is zero.

See it through and your odds of success improve dramatically from there, and along the way you are sure to learn things about the FAA, about aviation and about yourself that will make you a better pilot.

What is a Waiver?

To begin, let us consider the concept of an FAA waiver. The underlying premise is this: the FAA creates Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) to promote safety. Therefore, if you want to conduct an operation that is not allowed by the FARs—such as 14 CFR Part 107.29 (a): “No person may operate an unmanned aircraft system during night”—you must prove to the agency that your proposed operation will be at least as safe, or safer, than it would be if you followed the existing rules.

That’s it. At its most fundamental level, that is all we are trying to accomplish when we apply for a waiver. In order to achieve this goal, we need to understand two things: the unique hazards associated with night operations and the language the FAA uses to describe these hazards. Often, the second challenge can be the more formidable: the language of aviation and the FAA can seem paradoxical to the uninitiated.

For an example, we need look no further than the title of your waiver application. You want to fly at night, but you will apply for a “daylight waiver.” Why? Because you want to waive the requirement in the FARs that limit commercial drone operations to daylight hours.

Though it can be frustrating—bordering on nonsensical, at times—learning to speak this language means learning to think like a pilot, and that is essential to your success. If you wanted to make a good life for yourself in France, you would need to learn how to speak French. If you want to become a professional aviator, you need to learn how to speak aviation—because professional aviators are the ones who get their daylight waivers approved.

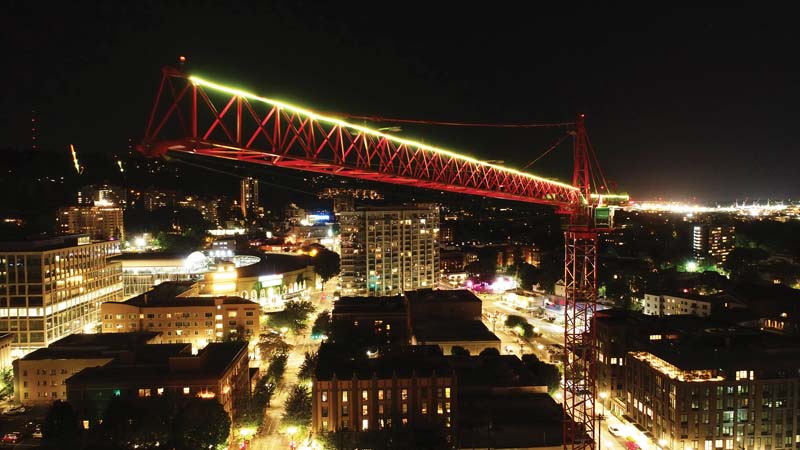

Darkness can imbue even ordinary objects with a sense of wonder and awe, such as this construction crane stilled for the night above the site of a new building rising in downtown Portland, Oregon.

Give ’Em What They Want

In order to be successful, an application for a daylight waiver must include several key elements:

● An explanation of how operations will be conducted safely;

● An explanation of where operations will be conducted; and

● Some mechanism to ensure members of the flight crew are acquainted with the hazards of night-time flying, including optical illusions that can lead to failures of perception and judgment.

What, exactly, is the FAA looking for in each of these elements? Fortunately, they have given us a series of loaf-sized bread crumbs to follow in the daylight waivers that they have already approved, which are available online. Don’t take my word for it. Type “FAA approved Part 107 waivers” into Google and see for yourself.

You can’t see the information that other applicants submitted to the FAA, but you can see the documents they received from the agency, describing the authorization provided to them by the waiver. As a standard component of these documents, typically appearing on page three, the FAA provides the following guidance, beginning with Point 8 under the “Specific Special Provisions” heading:

● All operations under this Waiver must use one or more visual observers (VOs);

● Prior to conducting operations that are the subject of this Waiver, the Remote Pilot In Command (RPIC) and VO must be trained, as described in the Waiver application, to recognize and overcome visual illusions caused by darkness, and understand the physiological conditions which may degrade night vision. This training must be documented and must be presented for inspection upon request from the Administrator or an authorized representative;

● The area of operation must be sufficiently illuminated to allow both the RPIC and VO to identify people or obstacles on the ground, or a daytime site assessment must be performed prior to conducting operations that are the subject of this Waiver, noting any hazards or obstructions; and,

● The small unmanned aircraft must be equipped with lighted anti-collision lighting visible from a distance of no less than 3 statue miles. The intensity of the anti-collision lighting may be reduced if, because of operating conditions, it would be in the interest of safety to do so.

In its own, oblique way, the FAA has handed us the answer key for the test we are about to take. Since nearly all approved daylight waivers include this exact same language, do you think these elements should be included in your waiver application? You betcha! Now that we have a clear idea of what the agency expects, writing a successful proposal is simply a question of filling in the blanks.

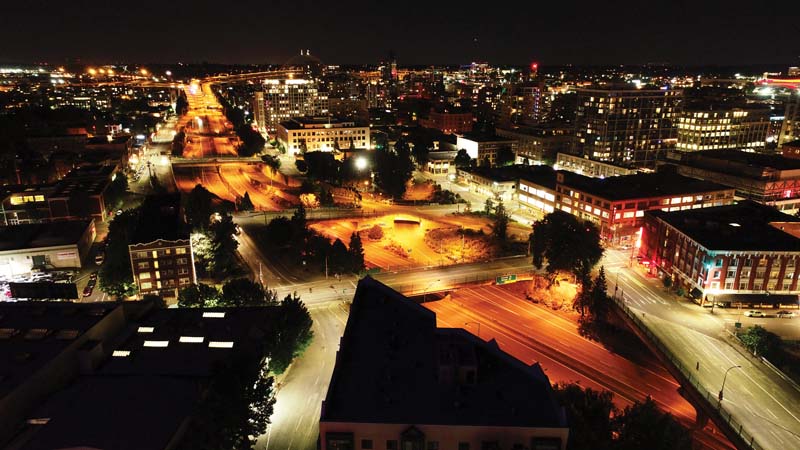

Set apart from its surroundings by its distinct, amber-colored lights, the I-405 freeway snakes through downtown Portland, Oregon below the level of the surrounding streets—giving the roadway its nickname: “The Ditch.”

Writing for the Government

When you sit down to compose the elements of your waiver application, it is helpful to think of the person who will read it, and decide whether it is approved or denied, as a friendly alien from outer space. They are intelligent, they want to be helpful, but they have absolutely no context for anything you are saying—unless you make it explicitly clear.

Take nothing for granted. Assume that they do not have access to the Internet or any other means of ascertaining even the most basic facts, unless you provide them. This may seem tedious or annoying, but remember, this is a test: the FAA needs to be convinced that you have thought carefully about what you are proposing to do, and that begins with a command of all the basic facts.

As you are developing this content, keep in mind that both the safety explanation and the proposed location write-ups are limited to 15,000 characters each. That sounds like a lot—and it is, but it isn’t infinite. Here is an example: so far, the main body of this story, discounting sidebars and photo captions, is about 7,500 characters—or about half of the total you have available for your safety and location descriptions. On a word processor, that works out to about two pages of single-spaced, Times New Roman text in 12-point type. Typically, the character count for a document is available alongside the word count under the “Tools” tab.

Also, be sure to take full advantage of whatever grammar and spell-checking tools you have available, especially if professional writing isn’t a part of your daily life. The meaning of a misspelled word or noun-verb disagreement will likely still be understood, but it will raise questions about your competence and may cause the reviewer to cast a skeptical eye toward the rest of your application.

Finally, there is no substitute for a human editor, who can help you clarify and refine your ideas. Plainly someone with a background in writing would be preferred, but just getting a second set of eyes on your material will make it better. You might consider either someone who knows nothing about drones—to see whether or not you’ve passed the “friendly alien” test—or someone who knows a lot about drones, who may be able to offer specific, technical guidance.

Recognize that writing a waiver application will necessarily involve writing. Whether you have a PhD in English literature or you haven’t written an essay since you graduated from high school, you must reconcile yourself to this fact: there are no shortcuts to be had.

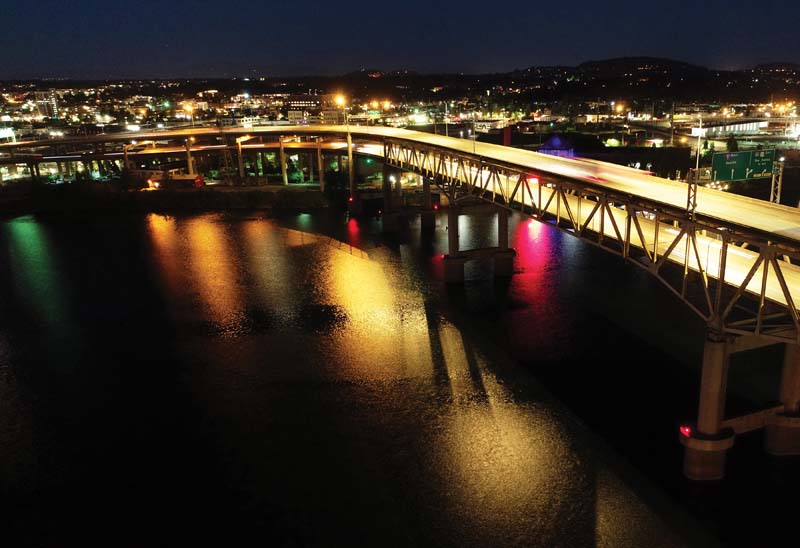

The Marquam Bridge crosses over the Willamette River in downtown Portland, Oregon—carrying the I-5 freeway on its long trek from San Diego to the Canadian border. Capturing an aerial perspective of the illuminated span at night provides a contrast with the dark waters of the river below, like a silver ribbon wrapped around polished onyx.

Safety Explanation

One of the two explicitly required components of a successful daylight waiver application, the safety explanation is your opportunity to describe for the FAA how you intend to ensure the safety of flight operations conducted in darkness. Again, we’ve already received some valuable hints from the agency itself in the waivers it has already improved.

Using a VO and anti-collision lighting are mandatory, the location where you will be flying must be illuminated sufficiently to see and avoid obstacles—or it must be scouted during daylight hours—and the flight crew must be trained to recognize the hazards inherent in night operations.

Write something down about each of those. Begin by describing the role of the VO. What will he or she be doing during the flight? How will he or she determine the heading of the aircraft? What types of hazards will he or she watch for? How will he or she communicate with the RPIC? What experience is required to serve as a VO on a night flight? How will the VO be trained to recognize night-time optical illusions? How will this knowledge be demonstrated?

When it comes to training and demonstrating its effectiveness, you might choose to follow the lead of the FAA. When it wanted to confirm your ability to follow the rules, read sectional charts and recognize hazards, it administered a test, which you passed in order to become a certified commercial operator. Could you develop a test to be administered to VOs prior to their deployment on night missions? What would it look like? Would they need to re-take it at certain intervals to maintain currency? How will those results be documented?

These very same questions, and more, will also need to be answered for the RPIC, so perhaps you decide to develop standards that apply to ever member of the flight crew. Or, maybe the RPIC will be required to meet standards that are even more strict, in terms of logged flight time, documented training, or some other qualification.

Next, write something about the anti-collision lighting system you intend to use. How is it powered? How will be attached to the aircraft? How do you know it is visible for three statute miles? Will you trust the information provided by the manufacturer? Will you conduct your own test of its capabilities and self-certify the result?

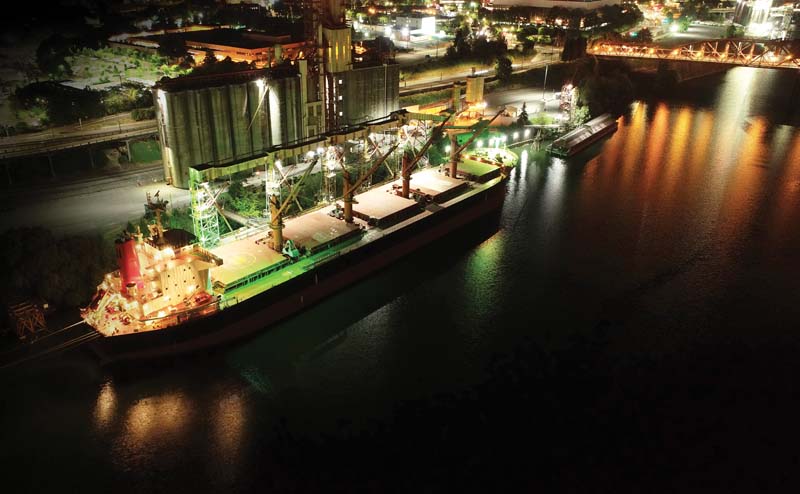

In the black of night, a freighter anchored along the bank of the Willamette River in downtown Portland, Oregon, takes on a shipment of grain bound for Asia. By volume, the city moves more cargo than any other port on the West Coast.

Questions and Answers

Turning your attention to safety more broadly within your explanation of the subject, you can start by addressing a couple of questions you know the FAA is looking for you to answer: How will you recognize hazards in the environment? Will the environment be sufficiently well-lit that you can see them? If it is not a well-lit environment, will you scout it during the daytime to identify hazards in advance?

Next, think about your drone. What aircraft are you flying? Is it a multirotor? Fixed-wing? A blimp? How much does it weigh? What is its maximum speed? What is its effective range? How long can it fly on a single battery? How can the propulsion system be shut down immediately in an emergency?

As you complete your safely explanation, describe one aircraft in detail, but then give yourself the option to self-certify other aircraft in your fleet once your waiver is approved. This will provide you with flexibility moving forward as new technology emerges and you purchase additional aircraft.

There are other safety questions that must be addressed, as well, including many of the same problems that could emerge on a daytime flight: How will you ensure the aircraft remains within visual line of sight (VLOS) throughout the mission? What if the RPIC and the VO lose sight of the aircraft? What if the link between the aircraft and the ground control station (GCS) fails? What if a manned aircraft appears in the vicinity?

Think about everything you need to accomplish during a night flight and everything that could go wrong, write a question about it based on the examples provided above, and answer those questions. You can even include the questions in your safety explanation, to guide the reviewer through your thought process. Remember to make your answers detailed, clear and precise. The FAA can’t give you credit for information you do not include in your application, no matter how obvious it might seem to you.

Proposed Location

Under the terms of a daylight waiver, location can be defined very broadly. Whereas airspace authorizations necessarily deal with one particular patch of sky located in the airspace surrounding a controlled airport, your authorization to fly at night could cover the the vast majority of the United States’ total land area.

It is typical for daylight waiver applications to request, and be granted, permission to fly in all Class G airspace. Also, as a general rule, these waivers do not provide authorization to operate in any class of controlled airspace. Make both points explicitly clear in your application: you want access to all uncontrolled airspace, but not Class B, C, D, or E airspace. This can be written as the answer to a question, such as: “In what class of airspace will operations conducted under this waiver occur?”

If you wanted to, you could choose to limit your operations to a more narrowly defined geographic area, such as an individual farm, or a specific city or county. However, there is basically no advantage to this approach as the FAA has demonstrated repeatedly its willing to authorize operations in all Class G airspace. No matter how certain you are about your mission parameters at the time you write your application, it is best to maintain maximum flexibility for the future so that you are able to respond to unforeseen circumstances.

One issue you need to address in your proposed location write up is the fact that there are many thousands of small airports located in Class G airspace. You should develop a specific plan for operations near these airports and include it in your application. Describe how you will ensure the safety of your drone and crewed aircraft operating in the vicinity. How close to an airport do you have to be before deciding that you are “near” it? Will you contact the airport manager and make arrangements? Will you file a Notice To Airmen (NOTAM)? Will you acquire a hand-held aviation radio and listen in on the airport’s common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) to enhance your situational awareness? Will you add another VO to your flight crew?

Finally, your proposed location includes the maximum altitude that you wish to fly. You are required to answer this same question elsewhere in the application process. However, it is entirely appropriate to address it here, as well—you will never go wrong by including clear, detailed information, even when it borders on redundancy. Based on the agency’s prior decisions, the FAA seems well-disposed to granting daylight waivers up to the maximum altitude allowed for general drone flight operations: 400 feet above ground level (AGL).

From their aerial perch, small civilian drones provide a new perspective on the world, a perspective enhanced by darkness that instills within it an added sense of mystery and drama—even in a subject as simple as a city park.

Test Yourself

If you decide that you will use a test to verify the members of your flight crew possess sufficient knowledge of how human perception and physiology are affected by darkness to conduct safe night operations, you should include a copy of that test with your application. You will have the opportunity to upload files, such as a test, on the page where you verify your information and submit your waiver request.

The format of such a test, should you choose to create one, is entirely up to you. However, this once again provides you with an opportunity to follow the FAA’s lead, and by doing so improve your chances of success. As a certified RPIC, you have taken at least one Airman Knowledge Test (AKT) during your career, so you are well acquainted with the format: multiple choice questions, each with three potential answers—only one of which is correct.

You can use that same format for your own exam. If you have never developed an FAA-style test before, it can actually be a lot of fun, as well as teaching you something about how the agency thinks about testing. My own recipe for developing questions is to add equal parts officiousness and cruelty, with just a splash of black humor. With a little practice, you’ll be putting up numbers like pros, and keeping your team well-prepared to meet the challenges that come with flying after dark.

If you develop a test, be sure to include a copy of the answer key, as well as any administrative documents you will use to record the results. This is another opportunity to prove to the FAA that you take seriously the responsibilities that come with being granted permission to fly at night.

he brilliantly illuminated Tillicum Crossing in Portland, Oregon, stands out against the dark waters of the Willamette River, making it an ideal subject for night-time photography, either from the ground or in the air.

Own the Night

With a little research, a little hard work, a little patience and a little perseverance, you can join that tiny fraction of certified commercial drone pilots who are authorized to operate around the clock: in daylight and darkness. Whether your goal is to support public safety, capture dazzling aerial imagery or simply enhancing your portfolio of skills, earning your daylight waiver is an important step in your growth as a professional aviator.

Text & Photos By Patrick Sherman