An entrepreneur’s view of the future of rotordrones

To be a true, successful entrepreneur, the formula is simple: identify a need and then fill it. With the tidal wave in popularity of quadcopters and rotordrone technology, now is the perfect time to get your feet wet in a promising industry. Civilian use of drones is not just a clever concept, it is here now, and those who work out all the kinks and help make rotordrones mainstream will be at the top of the food chain.

Such a forward thinker is Marc D’Antonio of Terryville, CT, who already has an impressive résumé of starting successful businesses in niche markets. A professional commercial model maker, CGI designer, videographer, and photographer, Marc sees a future with skies filled with autonomous worker drones doing everything from delivering fast food to searching for lost hikers in the wilderness. But to get there, he knows there are a lot of pitfalls and challenges to overcome.

Above: Marc makes some fine-tuning adjustments to the prototype quadcopter in the FX Models workshop.

Tell us a little about your company.

FX Models came into being in 1994 as the result of building a radio-control model of the Alvin deep submersible submarine. We sold hull kits for the Alvin and it was very popular with RC modelers and museums. I received a call from a production company for the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) asking us to do RC submarine work in London for a mini-series on Alvin and other submersibles. This really propelled us into the commercial model manufacturing business.

After some newspaper articles were printed about our work, it wasn’t long before we started doing work for the Department of Defense. This side of the business has continued to grow, and we are involved with ongoing developments with the U.S. Navy.

FX Models has since diversified into the creation of computer-generated imagery, 3D modeling, also known as rapid prototyping, and producing animations for magazines and films. In our visual effects roles, we have worked with Academy Award winner Douglas Trumbull on projects such as feature films, commercials, and various drones that we are now beginning to develop.

I always wanted to move in the aerial drone direction because the possibilities are just about endless. We put together a team of scientists from around the country and are researching various drone technologies that will be useful for any drone in the market. To date, we have several proprietary devices and several provisional patents in the works.

What are the challenges you see going forward?

There is no doubt about it, flying drones is a lot of fun. Flying up to 400 feet and then looking back at yourself is, to say the least, a real hoot. But there are pitfalls to this technology. For one thing, your neighbors may not be happy with you launching a flying multirotor up and over their houses, especially if it gets away from you. Although rare, such “flyaways” are issues that need to be dealt with since they usually end with the loss of the drone.

Today’s autopilots are pretty sophisticated and do help with potential failures. To illustrate the problems a drone might experience, we need look no further than our own early prototype quadcopter. We created a prototype to test various autopilot systems and started out using the Ardupilot control system. This open source program is available online along with some hardware for less than $100. Later iterations of our drone, and one particularly bad “tumbleweed” session that totaled it, showed us that we had to overcome many potentially catastrophic failure conditions.

Newer breeds of autopilots now can manage all sorts of conditions. Low battery voltage will bring a drone back to its GPS-coordinated home/starting position. Losing radio contact will switch the autopilot into a variety of safe flight modes or trigger a return-to-home condition. Gone is the need to really play with and adjust the basic settings that control how autopilots will correct errant behaviors. Hands-off flight is quite normal now. In fact, if a pilot gets into trouble while flying, simply letting go of the control sticks can quickly stabilize many drones.

Collision Avoidance

One other very important facet of drone technology is collision avoidance. You can still fly your drone right into the side of your house or car. I want this possibility to go away. We are working on a system that will prevent you from flying the drone into yourself, your car, your pet, a tree branch, house, or anything else for that matter. While our two main avoidance methods are proprietary at the moment, I can say that the system is already working on the bench. Our prototype will use the system in flight tests to determine its range and, more importantly, its limits.

Problems abound with avoiding collisions. Many objects are hard to “see” depending on the object detection method you use. Some avoidance systems have used a visual method where small cameras look at the drone’s path ahead and determine, using a parallax effect, how far away something is, and if it presents a threat. Other systems use barometric pressure sensors to determine relative altitude during auto landings to estimate where the ground should be. Although easily tricked by wind, the sensors are pretty well established in the drone marketplace. True collision avoidance is a very promising upcoming field, and our system with hopefully revolutionize drone work.

Weight vs. Performance

Flying drones presents the pilot with a tradeoff, being that of weight versus flight duration. Let’s say you want to fly in a 5-mile loop with your drone, but you want to fly at 50mph. If you want to see what the drone sees via a first-person view video downlink, then you have to attach more hardware, which adds weight. If you want to record the video on board with a GoPro or other camera, then you have even more added weight. Weight is bad, so lowering it without compromising the airframe integrity is the goal, but this isn’t so easy to do in practice. We shortened wire leads to knock off some weight and this produced a measurable increase in flight time. Adding aerodynamic covers allowed us to fly faster, but at the expense of — you guessed it! — more weight. So, for the drone field to really mature, you can expect to see even more extremely lightweight carbon fiber being used in drone structures. But this is fairly expensive, especially when you get into 6-motor hexacopters and 8-motor octocopters. Weight will always be a factor.

One of our company’s needs is to fly very expensive film cameras for feature film work. These cameras are legacy systems created many years ago and were not originally made to fly on small aerial drones. Reducing the weight of these cameras by removing parts is not usually an option. Besides, the cameras are usually rentals that you can’t take apart.

Flight duration is the most important aspect of drone operations. Good pilots can fly without autopilots and manage their craft just fine. But when the battery runs out of juice, you’re coming down. The entire flight envelope and everything the pilot does revolves around the battery life. Any conservative pilot will make sure to keep an eye on the battery life, making sure there’s enough power to get back. The trouble is that even the best flight plans can fail, especially if there is an unaccounted headwind.

Some smart circuits already exist and others are constantly being developed to prevent most battery failure issues. One way to monitor systems is with readily available On-Screen Display products, which will transmit vital parameters like altitude, airspeed, heading, and battery life remaining. Seeing the voltage remaining can let the pilot know when to turn around and come home. These units are small and use little power, but they do add weight. It all adds up. In addition, pilots can also allow the drone to manage the battery transparently and simply make decisions for them when a low-battery threshold is reached.

We have always believed that the performance of stable-flying platforms will continue to improve as technology develops. It’s inevitable, whether we develop it or not. I know FX Models will be involved in driving needed technology forward with our add-on control and system modules.

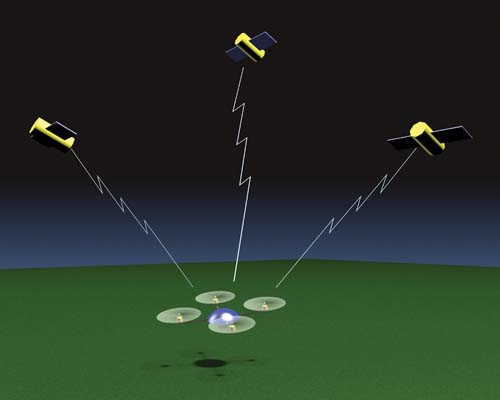

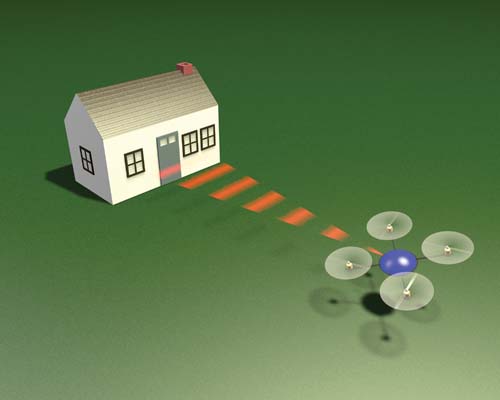

Above: GPS satellites allow drones to “know” where they are within a few feet relative to the ground and various way points. Below: FX Models is developing add-on onboard modules that will give drones the ability to “see” and avoid obstacles and then make corrections to their flight plans without the help of the pilot.

What does the future of rotordrones look like to you?

As the drone industry matures, we will see the advent of many new and improved autonomous platforms that will be able to lift larger payloads and carry them farther. Almost every aspect of daily life could be affected. We came up with a micro drone concept that can be stored in a backpack on the battlefield. They could literally be scooped out of the backpack, a dozen at a time, and thrown by hand into the air. The action of throwing would activate them so they could then zip down a city street in a warzone ahead of our troops to expose enemy positions. Designed to be disposable, if such technology had been available in Iraq, snipers and dug-in enemies could have been more easily exposed.

Domestic uses abound, and there will be no shortages of drones to fill the need. Lifeguards at the beach may rely on drones flying over swimmers to drop floatation devices. Autonomous lifeguard drones could look for sharks and other hazards to swimmers, detecting them automatically based on shape profiles seen moving over time. These examples are already being developed as university lab projects!

Above: On a cool New England morning, Marc D’Antonio puts in a test flight of one of FX Model’s quadcopters. Note the downlink telemetry On Screen Display attached to the transmitter. (Photo by Hunter D’Antonio.)

Battery life for the craft will also continue to improve, and eventually drones will fly back and plug themselves in when voltage drops to a certain level. Uses for future drones will include search and rescue, cinematic work, watching over neighborhoods with high crime rates, and much more. Drones can be implemented for a fraction of the cost of police helicopters for surveillance operations in local communities and within border enforcement protocols.

Making use of them legally, however, will be the trick. There are many hurdles to overcome and eventually laws will be put in place to protect privacy while helping, and not hindering, emerging industries that will rely on the safe operation of commercial drones. My suspicion is that the first round of drone laws will prove impractical to enforce. As with everything the government does, there is no simple solution and regulations will be complex. But one thing is very certain, drones in the hands of the enthusiast are here to stay.

By: Gerry Yarrish

Photos by: Peter hall