Networking Nanobots Take to the Sky By Michael York

The word “swarm” conjures up images of thousands of bees getting ready to launch an attack to protect their hive. Add the word “drone” and that image turns into something from a sci-fi horror flick. That same combination, however, is actually the very thing that’s starting to change people’s perception about drones. If you’ve seen an aerial drone show in person or online, it’s obvious that a swarm of autonomous flying robots

is not ominous. In fact, it’s just the opposite. The rapidly advancing technology is allowing for a whole new era of art in the sky.

So what exactly is a swarm? It’s basically a large group of individual things moving together as a unit. In nature, swarms come in many different forms. One of the most mesmerizing sights is that of a flock of starlings creating surrealistic shapes in the twilight sky (look up “murmuration” on the Internet if you’ve never witnessed it). Schools of fish behave in a similar fashion. And although we don’t think about it much, we humans swarm all the time: on the drive to work, at the store, or anytime we’re

dealing with crowds.

Ars Electronica Futurelab engineers and Intel are hard at work performing a final systems check prior to their Guinness World Record “Drone 100” flight. (Photo courtesy of Intel)

Researchers and engineers have been working hard to replicate swarm behavior in the robotics world, and there are endless possibilities for its use. What most don’t realize is just how difficult it is to replicate this subconscious behavior in a digital/mechanical fashion. It takes remarkable processing power to perform even simple autonomous synchronized flight between a dozen drones. Extrapolate that to hundreds—or thousands—and you can imagine the hurdle that needs to be cleared. Luckily, technology in computing power is advancing at a rate that makes it possible for hundreds of drones to fly together autonomously. Ten years ago, it was an amazing feat to see a just a few nano quads flying through suspended rings or other obstacles, aided by motion capture. Today, hundreds of autonomous lighted multirotors perform dynamic art shows in the night skies around the world.

On the evening of November 4, 2015, one hundred lighted drones eagerly await nightfall to take a record-breaking flight over Tornesch, Germany. (Photo courtesy of Intel)

How It Works

A little more than five years ago, researchers at the GRASP (General Robotics, Automation, Sensing, and Perception) Lab at the University of Pennsylvania made remarkable strides getting tiny drones to start flying with autonomy, thanks to the addition of onboard cameras and proximity sensors. Another big step toward having these little flying robots do it all by themselves was the decentralization of commands. A centralized program structure relies on a single drone to provide all information, such as the entire area map and obstacles that need avoiding, to each individual member of the group. This is a lot of information to pass along and can cause delays due to bandwidth limits. Also if something happens to the lead bot, the entire swarm is in trouble because

they are relying on that one drone for the data.

A swarm containing thousands of starlings is one of nature’s most mesmeric avian performances, something engineers someday hope to reproduce with drones.

In a decentralized system, each drone communicates with its immediate neighbor in a network style, which is faster because there is less data being passed along and it creates a more dynamic operation. This is similar to the way you move within a crowd: You pay attention to your immediate surrounding neighbors rather than to each and every person in the group. You don’t necessarily see obstacles in advance, but as they appear your “proximity sensors” tell you to move as necessary to avoid a collision with the obstacle and the persons around you, and they, in turn, do the same. This behavior also allows individuals to join or leave the crowd without greatly affecting the overall flow. To look at it another way, let’s say that 20 first graders are told to stand an arm’s

width apart from each other and make a circle. The circle is formed without them really needing to know the exact spot where each person is going to stand. Just knowing the

intended shape and distance from their classmate is enough to make this simple shape. If a student is added or subtracted, the size of the circle will adjust, again without having to tell anyone the actual dimensions needed to compensate for the addition or subtraction. This is obviously a simplified example, but you get the idea. This is a seemingly simple task for us humans, but onboard computers acting as the drones’ brain have to perform hundreds of calculations per second; this has certainly been a limiting factor in just how many of them can be safely flown at one time. Technological advancements tend to be exponential, so what seems difficult or impossible today will be rudimentary in the not-too-distant future.

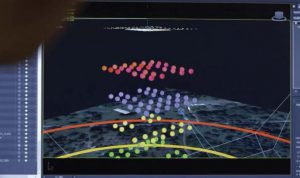

Planning a three-dimensional autonomous drone show is an art form in itself. Intel is constantly improving its software to make the transition from concept to reality faster and easier. (Photo courtesy of Intel)

Intel’s Swarming Drones

In the past few years, Intel has been making headlines with its own drone-swarm efforts. In 2015, a talented team of engineers from Ars Electronica Futurelab and Intel successfully broke the Guinness World Record by getting 100 drones to fly in an autonomous aerial display over an airfield in Germany, with an orchestra adding a fitting soundtrack. They called this the “Drone 100,” and a few months later, they re-created this feat over the desert in Palm Springs, California, to prove drone safety to the FAA. The first public display was performed in the night skies over the harbor in Sydney, Australia, with the Sydney Youth Orchestra providing musical accompaniment. Less than a year after the initial 100 took off, the team broke their own record by performing the Drone 500. Yep, you guessed it: They flew 500 drones. Although it might not seem like a big difference, it is a tremendous leap in less than a year. Improved algorithms and hardware led to an effective increase of the resolution on their sky canvas, allowing them to choreograph a very elaborate 3D light show. The computer programs that helped transform the multidimensional sketches in the designers’ minds into digital flight instructions for the drones progressed as well. What used to take months can now be done in weeks. Intel has also procured special FAA waivers that allow all the drones to fly using only one pilot, who monitors the ground computer as the drones perform their routine.

Who needs cranes or scaffolding when you can use a group of autonomous drones to create buildings? Here, multirotors from ETH Zürich build a nearly 20-foot-high brick wall.

Just like a group of people exiting a door, autonomous quadcopters can reconfigure their formation to allow them to pass through openings. Here is an early example from the GRASP Lab at the University of Pennsylvania.

Each space pixel (or “spaxel,” as Intel calls it) consists of a quadcopter called a “Shooting Star,” which Intel designed specifically for use in aerial light shows. This lightweight, roughly 15-inch-diameter drone is weather resistant and made almost entirely out of soft materials, with caged propellers to ensure safety in public displays. Adorned with LED lights that can produce four billion color combinations, the drones give the show’s designers a nearly endless palette with which to work.

The past and future of entertainment is melding. Here, a hundred autonomous drones dance in the night sky to the classically themed soundtrack performed by a live orchestra. (Photo courtesy of Intel)

The Future

At this point, we are at the very beginning of what I believe could become a whole new form of entertainment. The popularity of displays like Disney’s “Starbright Holidays” drone show is merely a hint of what is to come. While it’s hard to argue against the visceral effect of a good pyrotechnic show, hundreds of drones performing a synchronized aerial spectacle in the night sky is also hard to beat. As “resolution” improves, so will the complexities of the shows.

But entertainment isn’t the only place that will benefit from this technology. We’ve all seen the humorous depiction of what package delivery by a swarm of drones might look like, but it might very well be part of our future. Technology we used to laugh about is now something we can’t live without. People laughed at Motorola’s Bag Phones, which fit in a soft briefcase but allowed you to make calls while on the road. Those things will never progress beyond being a novelty item…right?

Then there is the humanitarian side. Search and rescue is one area that will benefit immensely by the use of drone swarms. Imagine the sheer area that a large group of camerae quipped multirotor bots could cover when searching for lost individuals in difficult terrain. Or inversely, a group of tiny drones could search for victims in damaged buildings that humans or search dogs might not be able to access safely.

Infrastructure will surely be another benefactor of these potential workhorses. The same benefit of large-area scanning that will benefit rescue missions can also be used to map terrain in both 2D and 3D. Autonomous drones have already been used to build mock structures out of bricks and other building materials. Imagine a group of drones building a shelter in areas that might be difficult to access via ground transportation. They could be used not only to fly supplies into position but also to build the structure itself. A group of flying cranes could also run cables across a gorge to help build a suspension-type bridge.

As you can see, a swarm of drones does not have to relay a negative connotation. Some of the greatest technological inventions had to overcome public-opinion issues, but once they took off (so to speak), people became accepting of and even reliant on them. I’m sure future generations will look back at this moment the same way we now reminisce about the time before smartphones.

Lady Gaga’s Halftime Light Show… with Drones

It did not take long for the rumors to start flying a few days before Super Bowl LI, when Lady Gaga hinted at what her halftime show would be about. Actually, it was her rooftop warm-up before her indoor show on 50-yard line that included the word “drone.” And what a light show that turned out to be.

The sky above the stadium roof at the Super Bowl was lit up by Intel’s Shooting Star drones (300 of them, to be exact) in a choreographed aerial light show that was as amazing to watch as it was to actually execute. Perhaps the most amazing thing of all is the fact that only one pilot with one computer controlled the entire swarm of light-emitting drones. (There is, of course, always a second pilot and computer on hand as

a backup.)

The software and animation interface on the Intel Shooting Star drone system allows a light show to be created in a matter of a few days or weeks depending on how complex the show’s animation has to be. Intel’s control programs use proprietary algorithms to automate the creation process. The programs use reference images to calculate the number of drones required, while also determining where each drone should be placed, to formulate the fastest paths needed to create the various images in the sky. The Intel Shooting Star drones are designed specifically for light shows and weigh only 280 grams—less than the weight of a volleyball. They feature built-in LED lights that can create over four billion color combinations. The Intel Shooting Star drones are constructed with a soft frame made out of flexible plastics and foam containing no screws, and the drones can perform for up to 20 minutes.

This was the highest the Intel Shooting Star drones have ever flown, and Intel received a special waiver from the FAA to fly their fleet up to an altitude of 700 feet. Intel also received an additional special waiver to fly the drones in the more restrictive class B

airspace. This was also a record-breaking event as this was the first time that drones have been used during a televised event and to complement an entertainment event of this scale.—Gerry Yarrish

Bridging The Gap

In the past, if you needed to build a rope bridge over a river, somebody had to get wet crossing to the other side in order to anchor the rope. In the not-too-distant future, you’ll just unpack a few drones and they’ll do all the work for you. A team from ETH Zürich’s Institute for Dynamic Systems and Control shows how it’s done.

Step one: The quadcopters anchor primary lines on both sides of the gap, then braid additional rope to reinforce the lower line.

Step two: As they go, the drones add the bracing structure that helps distribute the load

along the span.

Step three: Stabilizers are added to minimize side-to-side swaying. The rope bridge is now ready and, no one had to get soaked.