At most airports, if you walk out onto the tarmac carrying a drone, about the best you can hope for is to be asked, “What do you think you’re doing here?” At Eastern Oregon Regional Airport, however, they ask a different question, “How can we help?”

That’s because Eastern Oregon Regional Airport (PDT) is home to the Pendleton Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Range—and drones are their business.

“When people come out to do testing with us, they find that our control tower is very familiar with UAS,” said Darryl Abling, the range manager. “They have a lot of experience coordinating multiple, simultaneous UAS operations alongside our manned traffic—commuter airplanes, general aviation pilots, crop dusters, cargo flights, helicopters and the military.”

While the full integration of UAS into the National Airspace System (NAS) may still be years away elsewhere, it’s happening right now in Pendleton. Along with my Embry-Riddle colleagues, I had the chance to see it for myself over this past summer.

Members of the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Worldwide Campus Department of Flight control the movement of small UAS overhead from a makeshift mission control center set up alongside taxiway Foxtrot at Eastern Oregon Regional Airport.

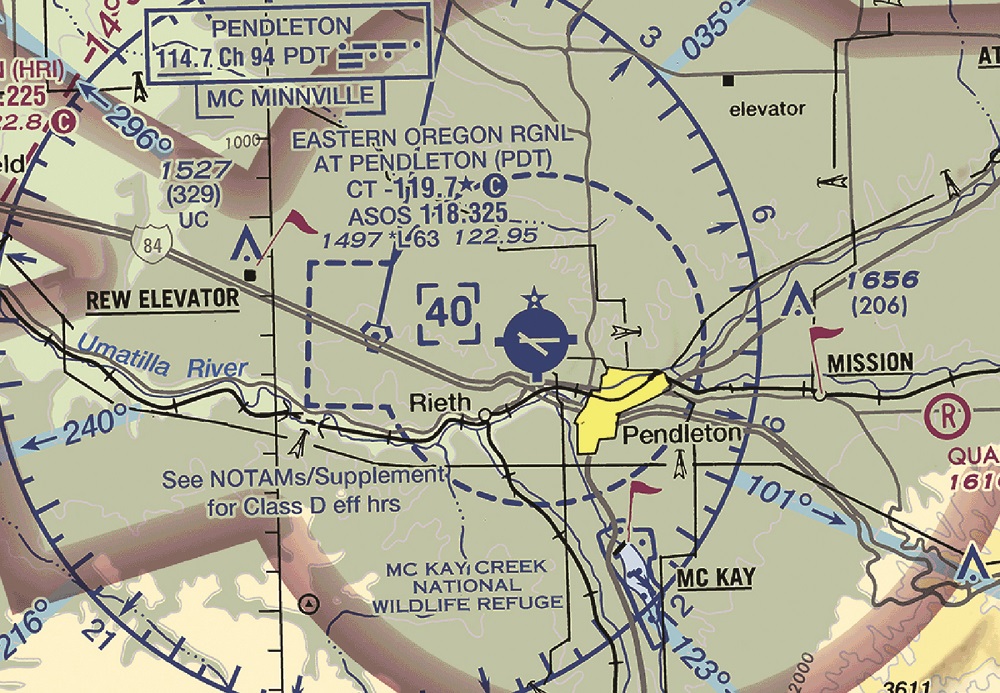

Eastern Oregon Regional Airport (PDT) is encircled by Class D controlled airspace, to an altitude of 4,000 feet MSL.

Stretching Our Wings

To better prepare our students for a future where UAS will be a mainstay in the aviation industry, the Embry-Riddle Worldwide Campus Department of Flight recently acquired a fleet of new drones—and not the sort that would fit easily inside a shoebox, or even a compact car.

These are big, heavy, sophisticated aircraft, including the DJI Agras MG-1P, a crop-dusting drone with a maximum takeoff weight of 54.7 pounds; the Lynx VTOL from SRP, originally developed for U.S. special forces; and, the Applied Aeronautics Albatross, a fixed-wing platform with four-hour endurance capable of accommodating modular payloads.

The only problem with big, heavy, sophisticated drones is that you need plenty of open space, as well as on-site resources—like a paved runway, water, power and the Internet—to test them. That was what brought us to Pendleton: the test range had everything we needed, and a whole lot more.

The range encompasses 14,000 square miles, and airspace is available from the surface up to 15,000 feet. It encompasses a wide range of terrain, including farmland, vineyards, orchards, forests and mountains. With an average of 347 days of visual flight rules (VFR) weather each year, it’s always a good day to go flying in Pendleton.

Our operations would be confined to the airport property, which itself required a big mental shift as a drone pilot. PDT is located in Class D airspace, and while there is a Low-Altitude Authorization and Notification Capability (LAANC) grid to allow for UAS operations in the vicinity, the squares at the airport itself have an altitude of “zero,” as you would expect.

However, in order to fly there, we didn’t go to the DroneZone on the FAA website and make our case 90 days in advance. Instead, we picked up a hand-held aviation radio, tuned it to the Pendleton tower frequency at 119.7 MHz and stated our intentions. Given that the FAA generally prohibits drone pilots from communicating on aviation frequencies, this was a very strange feeling indeed.

For the most part, the syntax was identical to what crewed aircraft pilots use, with one exception: Rather than using the absurdly long registration numbers the FAA assigns to drones to identify our aircraft, we adopted call signs. Regardless of its type or specifications, the first aircraft we launched became “Riddle 1.” If we launched another platform while the first one was still active, it was designated “Riddle 2.”

Eastern Oregon Regional Airport—identified as PDT on aeronautical charts—has flourished since it began hosting the Pendleton UAS Range beginning in 2013. About 150 people work full-time at the airport for its various clients, developing and testing new drone aircraft.

A light airplane departs Eastern Oregon Regional Airport while a member of the Embry-Riddle Worldwide Campus Department of Flight prepares to launch a UAS in the foreground.

After hosting numerous UAS test campaigns at the Eastern Oregon Regional Airport, range manager Darryl Abling has accumulated a substantial collection of challenge coins, laid out on his desk for visitors to admire.

Pendleton’s annual rodeo, known as the “Pendleton Round-Up,” is held in an outdoor arena of the same name the second week of September each year. The arena lies in a valley, just below the city’s airport, which is also the home base for the Pendleton UAS Range.

The following day, the aircraft that had been known as “Riddle 2” would become “Riddle 1” if we launched it first. If we were only operating one aircraft at a time, each of them would be referred to as “Riddle 1” in turn. Because we were flying rotorcraft, VTOLs and fixed-wing platforms, we also had to state at the outset what type of aircraft it was, so the tower knew what type of behavior to expect: hovering and slow maneuvers or continuous forward flight.

Starting Small

Today, the Pendleton test range is thriving, with 150 people working full time for various clients—most of whom are shielded by non-disclosure agreements—making it a key economic driver for the city. However, it had not always been that way. Not so very long ago, the airport was viewed as a drain on the city’s resources.

“I moved out here to work nine years ago,” said Steve Chrisman. “At that time, the city manager told me, ‘We can’t afford to have an economic development director and an airport manager, so you’ll have to do both.’ I didn’t know anything about aviation at the time, but I do know how to recognize an underperforming asset when I see it.”

Among the people Chrisman met was the commander of an Army National Guard unit based at the airport, which operates RQ-7 Shadow reconnaissance drones.

“He was in the process of securing permission to operate his Shadows at the airport, so the unit didn’t have to travel to the restricted airspace at Boardman in order to fly,” Chrisman recalled. “He said to me, ‘Look, civilian drones are about to become a big thing, and the airport would be a great place to test them.’”

Investigating further, Chrisman discovered that the FAA had put forward a proposal to establish UAS test ranges at different locations around the country, and he began to explore how Pendleton could become one of them. Ultimately, he linked up with sites located in Alaska and Hawaii to become part of what is today the Pan-Pacific Test Range Complex.

“For the first couple of years, there was very little activity at the range,” said Abling, who became the full-time range manager once its operations started to expand. “One of our early clients was Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. They did a lot of training with the Arctic Shark out here. It’s a 600-pound, fixed-wing platform used to study the atmosphere at high altitude. We also had Yamaha doing some work with their R-Max helicopters.”

Then, after two years of struggle, the dam broke: Airbus subsidiary A3 selected Pendleton to prototype and test its Vahana urban air mobility platform.

“They came here and made Pendleton their home,” said Chrisman. “They took over this big hangar and had people working here full time. Those are good-paying, aerospace jobs—something that any rural community would be excited to attract.”

Following Vahana’s success, interest in the range began to grow, according to Abling. “Ultimately, the UAS industry is still a small community,” he said. “Everyone has relationships with everyone else, even if they change companies, and so pretty quickly the word got around that Pendleton was a great place to do your testing.”

Radio Traffic

“Pendleton tower, this is Riddle 1, requesting clearance for takeoff from taxiway Foxtrot,” I said into the radio clipped to my vest.

“Roger that, Riddle 1, this is Pendleton tower. Does Riddle 1 need to roll, or does it go straight up?” came the reply.

My cheeks flushed—I had forgotten to specify what type of aircraft we were flying.

“Pendleton tower, Riddle 1. We’re flying a VTOL. It will make a direct ascent to 150 feet AGL and then transition to forward flight southeast of taxiway Foxtrot,” I replied, trying not to sound flustered.

“Riddle 1, Pendleton tower: you are cleared for takeoff, altimeter two-niner-niner-seven,” the voice came across the radio, unperturbed.

“Riddle 1,” I said, acknowledging the clearance.

One of my colleagues pressed the “Launch” button on his laptop, and the Lynx leapt into the air and ascended briskly before its main motor powered up and pushed it silently out over the wheat fields to the south. Another mission had begun, more or less successfully.

Our base of operations on the airport grounds was a gravel pad with water and electrical hook-ups, built specifically to support UAS operations—one of five along the south edge of taxiway Foxtrot, which served as our “runway” for the duration of our stay in Pendleton. However, it was a resource that we had to share. Occasionally the tower would call to let us know that a small jet or a turboprop was departing on Runway 25, and we needed to make the taxiway available for them.

For all of the drama around the supposed conflict between crewed and uncrewed aircraft, it was a remarkably seamless process. We were all aviators, each of us placing our full confidence and trust in one another as professionals, dedicated first and foremost to the safety of flight.

Our operations comprised just a tiny fraction of the overall UAS activity at the range, according to Abling.

“We broke 1,000 operations per month for the first time in May,” he said. “Somewhere between 600 and 1,000 operations per month has been pretty typical lately. However, based on our scheduling and what our customers are telling us, we’re expecting that to go up to between 2,000 and 2,500 operations per month next year.”

Fast Mover

According to Abling, a key to the range’s success is its ability to “move at the speed of business.”

He explained, “I think it’s the ability to come in and start flying almost immediately that makes us attractive to prospective customers. When somebody contacts us about flying at the range, we respond with two documents: a mission-requirements template and an expedited-project questionnaire.”

The first seeks to understand what the prospective client hopes to achieve and what resources they require. That includes airspace, supporting infrastructure, office or hangar space, a mobile mission control center or even a remote site off the airport.

Eastern Oregon Regional Airport laid fallow for decades following the aviation deregulation in the 1980s, but recent years have seen a burst of new construction as it has emerged as a hotbed for UAS testing. Here, the groundwork is being laid for a new 72-room Radisson hotel, set to open in the first quarter of 2022.

A pair of Yamaha Fazers—the latest iteration of the company’s long-serving crop-dusting R-MAX UAS—are stored in a hangar that housed the planes used by the Doolittle Raiders during World War II.

“With that, we are able to give them a rough order of magnitude for pricing,” he said. “It helps that our pricing is very competitive compared to government ranges. They can come here and fly without spending a boatload of money on the range itself.”

The expedited project questionnaire asks about the aircraft the client intends to test: What frequencies does it use for control and telemetry? What is its lost-link behavior? How fast does it go? What is its maximum speed and altitude?

“We’ve never had to say ‘No’ to anybody based on what they tell us, but we need to understand those things,” said Abling. “If the aircraft is under 55 pounds, it is immediately covered under our blanket Certificate of Authorization (COA) from the FAA. Then the University of Alaska, which heads the Pan-Pacific Range, writes up an airworthiness statement that allows the vehicle to be tested on the range.

“If it weighs more than 55 pounds, it has to be specifically listed on our COA,” Abling said. “We have a lot of different aircraft types that are already on that list, but if this is a new one, it requires a paper-and-ink change to the COA, and that takes between two and three weeks, depending on how busy the FAA is.

“The upshot is: If you’re small, we can get you flying in two or three days; if you’re big, it’s going to take a couple of weeks.”

The surge of business at the range has led to a building boom at the airport. Work was recently completed on 30,000 square feet of new hangar space. On the north side of the field, flanking a runway dedicated exclusively to UAS, a 150-acre industrial park is now ready for new tenants, with water, power and high-speed-data connections available on site.

“Right now, we’re in the process of building a hotel here on the airport property, right across the parking lot from the terminal building,” said Abling. “It’s going to be a 72-room Radisson, and when that opens in the first quarter of 2022, it’s going to make the range even more attractive. People will be able to fly in from Portland on Boutique Air, check into the hotel, which will have its own restaurant and bar, and then walk out onto the field to do their testing.”

Let ‘Er Buck

Even apart from the airport—with its storied past and bright future—Pendleton is a town that punches well above its weight in terms of its history and culture. Incorporated on Oct. 25, 1880, with 730 inhabitants, among the town’s first major industries was a scouring mill, where wool from local sheep herds was washed and cleaned before being shipped out by rail.

The operation expanded into a full-service woolen mill in 1895, weaving blankets and robes for the Native American tribes in the region. Today, the Pendleton Woolen Mill brand is known worldwide for its quality wool apparel—and every item sold still includes a label telling the customer that it is “Warranted to be a Pendleton.”

In 1910, Roy Raley, a local attorney with a showman’s flair and a keen mind for business, established a rodeo the second week in September. The tradition continues to this day as the world-famous Pendleton Round-Up, which brings in visitors from all over the world and has been voted America’s best outdoor rodeo for the past five years.

The town’s Old West spirit is still very much alive today, as I discovered along with my Embry-Riddle colleagues, exploring the town after a long, hot day on the tarmac. Life-sized statues of the many colorful characters who have shaped the town through the years dot the sidewalks, and the restaurants and bars pay homage to the town’s frontier history.

It’s an attitude that even extends to the UAS range, according to Chrisman, who became the town’s full-time economic development director once the range was well established.

“Pendleton is still a handshake kind of town,” he said. “That ‘git ’er done’ attitude still prevails here.”

That was certainly our experience. During our visit, the Albatross went awry when we attempted an autonomous take-off, tearing a jagged chunk out of the its propeller when it careened off the runway. Remember, we were there to test these aircraft—and testing necessarily involves the possibility of failure.

The Lynx VTOL from SRP ascends vertically for a test flight above Eastern Oregon Regional Airport, where crewed and uncrewed operations have been seamlessly integrated as part of the Pendleton UAS Range.

The following day, we got to talking with another UAS crew operating at the range. We discovered that they also had an Albatross in their fleet, and they volunteered a spare propeller to get us back up and flying, along with some helpful advice.

That was one tiny example of what economists call the “cluster effect.” When a certain type of business is established in a geographic area, it becomes easier for similar businesses to get started and grow in that same area. That’s why automobile production was concentrated in Detroit for the first half of the 20th century, or why so many tech firms are based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Of course, that raises the question of how a business cluster gets started in the first place. Economists are divided on the subject, but Chrisman seems to think it could have something to do with pure, old-fashioned frontier stubbornness—at least in the case of Pendleton.

“There have been some bumpy spots along the road,” he said. “But the City Council has been absolutely supportive of the range from its inception, even before there was a lot of activity. They moved forward on faith, and that has absolutely paid off.”

BY PATRICK SHERMAN

Patrick Sherman is a full-time UAS instructor at the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Worldwide Campus Department of Flight.