Understanding FAA, operational, and personal LIMITS is key to safe flying

At 7:20 p.m. on Sept. 21, 2017, a DJI Phantom 4 had a midair collision with a U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopter flying off the shoreline of Staten Island, New York. The collision damaged a main rotor blade and a window on the upper left-hand side of the helicopter, forcing the crew to make an emergency landing at Linden Airport in New Jersey. The Army helicopter was operated by the 82nd Airborne Division and was one of two Black Hawks assigned to a security patrol during the United Nations General Assembly meeting in New York City in advance of the U.S. president’s arrival.

HOW IT HAPPENED

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) launched an investigation into the crash, the first incident of its type to have occurred in U.S. airspace. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) confirmed that it was assisting with the investigation but said that the U.S. Secret Service was the lead agency for media inquiries. The Federal Bureau of Investigation said that it was assisting the U.S. Army’s investigation. The New York Police Department said it was also cooperating with the investigation, but it referred questions to the FAA and the U.S. military.

The NTSB Aviation Incident Final Report stated that one motor and a portion of an arm of a Phantom 4 was found in the engine-oil cooler fan by Army maintenance personnel. Using the serial number inscribed on the motor, federal investigators were able to identify, locate, and interview the Phantom’s pilot, who has turned over flight data from the ground controller.

The NTSB Report stated the Phantom’s pilot intentionally flew the aircraft 2.5 miles away, well beyond visual line of sight. The pilot of the Phantom 4 was flying for recreational purposes and did not hold an FAA Remote Pilot certificate or a manned aircraft pilot certificate. Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 101 mandates hobby and recreational pilots maintain visual contact with their aircraft at all times and not interfere with the operation of manned aircraft.

While the airspace in the area of the flight is uncontrolled (Class G), it was underlying a shelf of the Class B airspace and a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) issued by the FAA was in effect at the time of the incident. The NOTAM established a Temporary Flight Restriction (TFR) due to the United Nations General Assembly meeting. The TFR restricted operations within the lateral limits of the New York Class B airspace. In addition, another NOTAM was in effect establishing a VIP Presidential TFR over the crash site. Both TFRs included a prohibition on model aircraft and unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), and the Phantom pilot literally flew from one TFR into another.

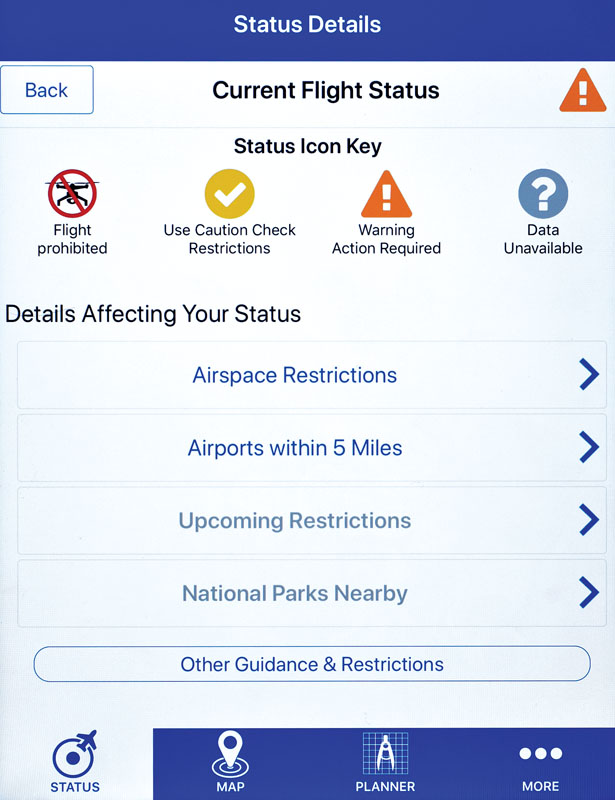

Warning screen displayed on the B4UFLY app when drone is in controlled airspace.

Message from the FAA displayed when opening the B4UFLY app.

Warning from the FAA to all drone users displayed when opening the B4UFLY app.

OPERATOR ERROR

During the interview by federal authorities, the Phantom pilot stated that he knew to stay away from airports, and that he relied on the DJI GO 4 app to “let him know if it was OK to fly.” He said he knew that the Phantom should be operated below 400 feet. When asked about the TFRs, he said he did not know about them and that the app did not give any warnings on the evening of the collision. The Phantom pilot said he was not aware of the significance of flying beyond line of sight and again stated that he relied on the app display. He said he did not see or hear the pair of helicopters involved in the collision but admitted knowing that helicopters frequently flew in the area.

Although the pilot stated that he knew not to fly above 400 feet, his flight logs revealed that he had flown as high as 547 feet at a distance of 1.8 miles earlier on the evening of the incident. In addition, even though the Phantom pilot said that he knew there were often helicopters in the area, he still decided to fly beyond visual line of sight, which demonstrated his lack of understanding of the potential collision hazard with other aircraft.

The DJI GO 4 app for the Phantom 4 includes a feature called “Geospatial Environment Online” (GEO), which is designed to help pilots avoid certain types of airspace. GEO provides pilots with real-time guidance about areas where flight may be limited by regulation, such as controlled airspaces and TFRs. Locations that raise security concerns, such as prisons, nuclear power plants, and military bases, may also be identified. When available and activated by the pilot, a message is displayed on the control device identifying the type of airspace.

According to DJI, “The GEO system is advisory only. Each user is responsible for checking official sources and determining what laws or regulations might apply to his or her flight.”

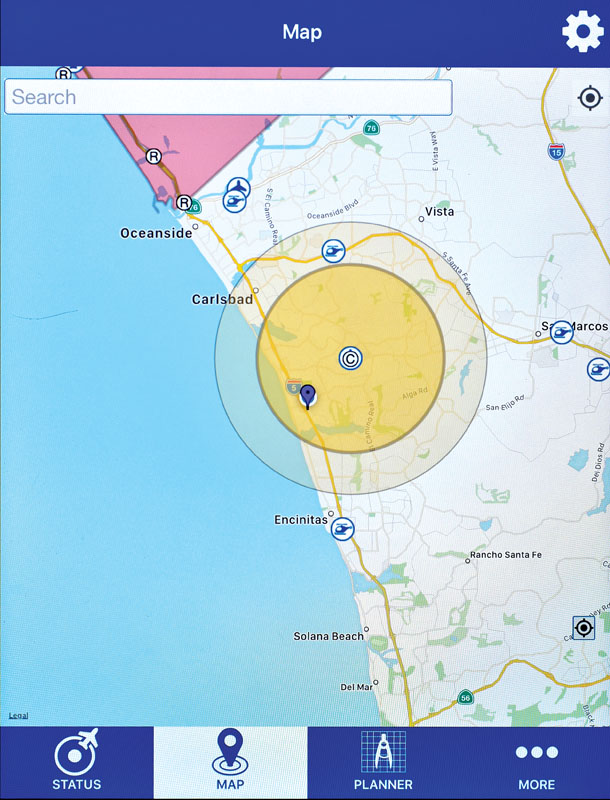

NTSB investigators also determined that, at the time of the incident, the TFR airspace-awareness functionality within GEO was not available. DJI had temporarily disabled the feature in August 2017 because of technical problems, and it was restored in October 2017. DJI did not issue any notice to users that this advisory function had been disabled. The NTSB further emphasized this feature is intended for advisory use only, and UAS pilots are responsible at all times to comply with FAA airspace restrictions. Sole reliance on advisory functions of a non-certified app is not sufficient to ensure that correct airspace information is obtained. The best way to locate airspace restrictions is to use the FAA’s B4UFly mobile app for recreational users or AirMap for Part 107 operators.

The NTSB determined the probable cause of this incident to be “the failure of the sUAS [small unmanned aircraft system] pilot to see and avoid the helicopter due to his intentional flight beyond visual line of sight. Contributing to the incident was the sUAS pilot’s incomplete knowledge of the regulations and safe operating practices.”

FAA AND OPERATIONAL LIMITS

There are many lessons to be learned from this incident, and everyone, especially the Phantom 4 pilot, should be grateful there were no injuries or fatalities. Clearly, there is still a lack of understanding of “safe operating practices” among some members of the drone community, in particular regarding flight limitations.

There are basically three types of limitations in aviation. The first set of limits is imposed by the aircraft manufacturer and may be called “operating limits” or “aircraft limits.” The second category are regulatory limits imposed by the FAA or other government agency, and the third category are personal limits.

All manned aircraft have operating limitations imposed by the manufacturer. Full-size aircraft have limits that are carefully tested and proven by FAA, and are certified for operation within those limits. Since drones are not certified by the FAA, it is simply up to the manufacturer to do its own testing and determine the operating limits.

Drone manufacturers are not required to provide these limits to the user, so these limits are often unknown. DJI has been making an effort to provide this information in its user manuals but the limits are not presented in a standard format as they are for manned aircraft. A closer look at some of these limits in the user manual for the DJI Phantom 4 will help explain the relationship among the three types of limits:

The maximum altitude is 1,640 feet. It is widely known (hopefully) that the regulatory limit for flying drones is only 400 feet. The Phantom 4 has two flight modes: P-mode and A-mode. The 400-foot-altitude limit is preset in the P-mode, and it is not possible to exceed that limit. If the A-mode is selected, it is possible to fly the Phantom 4 up to 1,640 feet above the takeoff point. The standard traffic-pattern altitude for manned aircraft while in

the vicinity of an airport is 1,000 feet, so this would put the drone in an extremely dangerous flight area.

The maximum range is 4.3 miles. FAA regulations state the aircraft must be kept within visual line of sight. This regulation is interesting because the FAA does not give a specific distance for this limit. The actual distance will depend on the size of the drone, lighting conditions, and eyesight of the pilot. In other words, this regulatory limit is established by the pilot’s personal limits. The pilot needs to determine this limit during each flight, and the actual distance may vary depending on the location and conditions. Since most drones now have telemetry data displayed on the pilot’s ground controller or smart device, it is possible to know the drone’s exact distance at all times. Pilots can and should know the actual distance at which their drone becomes difficult to see and then reduce that number by 10 percent or more as a safety margin.

The maximum wind speed is 22mph. While the FAA does not have any specific limit for flight in high winds, it does mandate that all aircraft are flown in a safe manner. Intentionally operating in winds more than 22mph with a Phantom 4 could be considered operating in a careless and reckless manner. Since the dawn of aviation, pilots have been concerned about high winds, and experienced pilots are always aware of both current and forecast conditions. The maximum wind speed for each drone is a critical limit because, once it is exceeded, the drone will not be able to maintain position, even in GPS mode.

Pilots should be aware that the wind speed is not always constant, and strong gusts of wind are unpredictable and may push the drone away and even out of sight. Wind speed usually increases with altitude, and the actual wind speed above surrounding ground structures may be significantly higher than expected. When flying on windy days, it is important to be prepared to react with a memorized emergency procedure. In most cases, it is best to cut the throttle immediately and descend rapidly since wind speeds usually decrease the closer you get to the ground. Maneuvering to an area that is protected from the wind (such as the downwind side of a building or structure) will also help maintain control during the landing. Having a personal limit for maximum wind speed is important, and inexperienced pilots should fly only in calm winds.

Map display page on the B4UFLY app showing a drone within controlled airspace

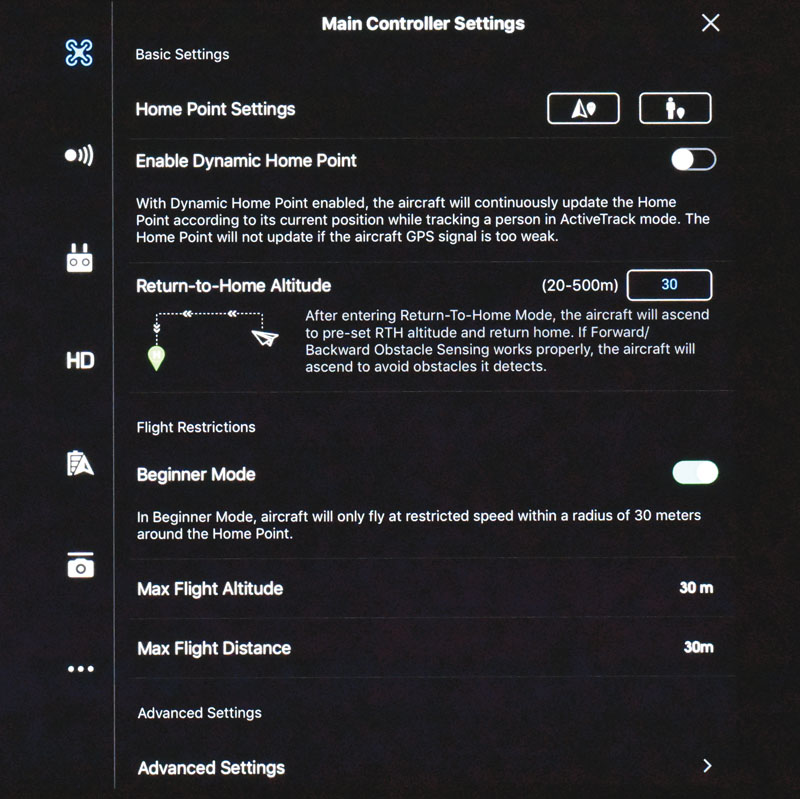

Beginner Mode selected by the user on the DJI Go4 app. Both altitude and flight limits are set to 30 meters 100 feet by default.

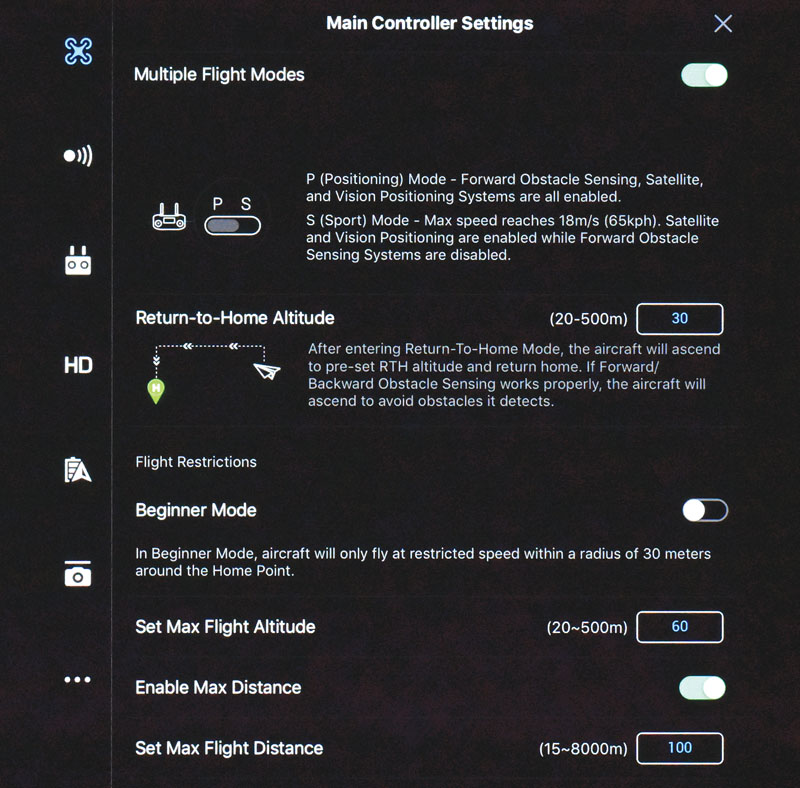

Flight altitude and distance limits manually selected by the user on the DJI Go4 app.

PERSONAL LIMITS

Novice drone pilots may find it difficult to set personal limits because they just don’t have the experience to make an informed decision. Keep in mind that determining your personal limits is part of the learning process. When pilots start to think about setting personal minimums, they usually start with weather conditions. Personal limits are your limits, tailored to your experience, strengths, and weaknesses.

Personal limits will also change based on your level of proficiency. For example, a pilot who has been flying in high winds during the day for many months will become more proficient in these conditions. Similarly, a pilot who has been flying at night in calm winds for many months will become more proficient operating in the dark. Clearly, the pilot who flew only during the day would not be proficient at night flying and vice versa.

The responsibility for determining proficiency is a judgment call by the pilot, and this is something that comes with experience. An individual’s definition of “proficient” may vary according to his or her skills, knowledge, and experience. In the absence of firm guidance, it’s up to pilots to determine whether or not to go flying and what conditions are acceptable to avoid a situation that exceeds their skill level or the drone’s limits. Personal limits are determined to help guide pilots through the decision-making process.

Once your personal limits have been determined, some of them can be programmed into the DJI GO 4 app. Maximum flight altitude and radius limits may be put in the app and changed at any time. If you are inexperienced, DJI also created the Beginners mode, which restricts flights to an altitude and height of 30 meters (100 feet). It is important for pilots to identify and understand their personal limits to the same degree they concern themselves with aircraft limits and regulatory limits. After all, does anyone want federal agents and investigators to knock on the front door?

Text & Photod by Gus Calderon