Pilot Report

As a pilot, the most important decision you will ever make is whether or not to go flying in the first place. When you commit a machine to the air, the only absolute guarantee you have is that it will return to the ground, and where, when, and how are variables that you may or may not get the opportunity to influence. It’s like the old aviation adage, “Takeoffs are optional. Landings are mandatory.”

In February, on the day after Valentine’s Day, I had occasion to reflect on that aphorism as I stood in the rain, deciding whether or not to complete a mission I had accepted from one of my longest-standing clients, the Human Access Project (HAP) of Portland, Oregon. A nonprofit organization, HAP’s goal is to connect the city with the Willamette River, providing access points to the water and encouraging people to take the plunge.

However, mid-February in the Pacific Northwest is nobody’s idea of good swimming, with both the air and water temperature hovering about 10 degrees above freezing. Nevertheless, for the past couple of years, a few hearty souls have committed themselves to the river as part of the HAP Valentine’s Day Dip celebration. My mission was to capture aerial video of the scene: brave Oregonians hurling their pasty, sun-deprived winter bodies into the murky waters of the Willamette.

Unfortunately, the weather had other ideas. Steady rain was falling when I arrived at the area of operations, and according to the forecast, it wasn’t going to let up any time soon.

A high-quality case is among the best investments you can make after you acquire your own drone. It keeps all of the parts and accessories in one place while it protects the aircraft during transportation and storage. And, it’s waterproof!

Quick Specs

Mission Type: Aerial imaging

Location: Portland, Oregon (N45°29’33” W122°40’37”)

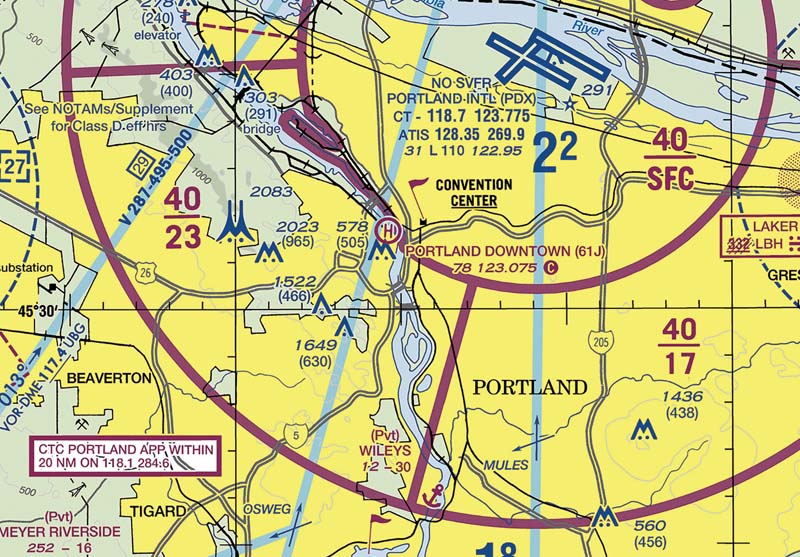

Airspace: Class G to 700′ AGL

Clearance: None required

Monitored frequency: 123.075 MHz Portland Downtown Heliport (61J) CTAF

METAR Text: KPDX 151753Z 18008KT 10SM -RA FEW017 BKN032 OVC040 06/04 A3022

Platforms: DJI Phantom 4 Pro+, Autel Robotics Evo Remote pilot in command: Patrick Sherman, Roswell Flight Test Crew

This mission occurred in Class G airspace, underneath a shelf of Class C airspace extending outward from Portland International Airport (PDX), stretching from 2,300 feet to 4,000 feet above mean sea level (MSL).

Whether or Not to Fly—Weather or Not

Among the first steps you need to take on any mission is to assess the flying environment. What potential hazards do you see? Tall trees or above-ground utilities? Potential sources of radio frequency or electromagnetic interference? Other air traffic? People on the ground? And, of course, do the current weather conditions permit safe flight operations?

From a regulatory perspective, I was good to go. The closest reporting station, Portland International Airport (PDX), indicated 10 statute miles of visibility with a few clouds at 1,700 feet above ground level (AGL), well in excess of the minimums required under 14 CFR Part 107. Furthermore, there is no rule against flying in the rain, but that doesn’t necessarily make it a good idea.

A few drones, such as the DJI M200 series, the PowerEgg X, and the Evolve 2 from XDynamics, are actually weatherproof. The PowerEgg can be enclosed in a waterproof housing, and the M200 and Evolve 2 both have IP43 ratings, meaning that water splashing against their airframes from any direction will not affect their performance.

However, I wasn’t flying any of those platforms. Instead, I had a DJI Phantom 4 Pro+ with an Autel EVO as backup, neither of which is rated for rain. That said, most multirotors can tolerate some precipitation. The motors, which are the most exposed electrical components, are just fine in the rain. The most likely point of failure are your electronic speed controls, which vary the speed of your motors. One drop of water in the wrong place on these high-voltage components could mean an abrupt end to your flight. Another issue in the rain is the cameras: Get water droplets on your binocular collision avoidance system and it could malfunction or stop working altogether. Water on the lens of your image capture camera doesn’t pose a direct threat to flight operations, but it will wreck your video, which is the reason for putting a machine up in the first place.

This mission occurred within seven miles of Portland International Airport (PDX), just south of downtown Portland on the west bank of the Willamette River. However, no authorization was required because it occurred beneath a shelf of Class C airspace with a floor of 2,300 feet above mean sea level (MSL).

Know Means No

The hardest test that you will ever face as a pilot is saying “No” to a client. Perhaps the event you have been asked to record only happens once a year, which was the circumstance I faced on this occasion, or maybe a lot of resources and money have been spent to arrange the scene you have been hired to capture.

As a professional aviator, you must always put safety ahead of every other consideration, and you must always be prepared not to fly, if that is what safety demands. It’s easy to check that box when you’re taking a test, or say it when you’re talking with your fellow pilots about your decision-making process. It is a whole other thing to do it in a real-life situation, but you must always be prepared for it.

In this case, I was lucky. The event organizer was clearly hoping that I would be able to get some aerial video, but after years of working together, he trusted me and was prepared to accept my judgment. So, there was no danger that external pressure would distort my decision-making process, but there was another person who could cause an unsafe operation—me.

When you were studying for your Part 107 exam to become a remote pilot in command, you hopefully had the opportunity to review the five hazardous attitudes that can afflict pilots: Anti-Authority (“Don’t tell me what to do!”), Impulsiveness (“Get it done quick!”), Invulnerability (“It won’t happen to me!”), Macho attitude (“Watch this!”), and Resignation (“What’s the use?”).

The dark secret that perhaps no one has revealed to you yet is that every pilot, including you and me, is specifically vulnerable to one or more of these hazardous attitudes. You will do yourself a favor by figuring out which one it is right now, and developing strategies to mitigate it.

For me, it’s invulnerability. In my moments of weakness, I manage to persuade myself that even if I make stupid decisions, I’ll come through it unscathed, because of who I am, or what I have done, or where I have been, or all the hours in my logbook. The truth is, stupid decisions break flying machines, and I’ve got a box of broken parts to prove it.

So, as the clock ticked down to the start of the event and I continued to assess the situation, I was on guard for the little voice in my head telling me that everything would be OK if I decided to fly because, “Hey, I’m me!”

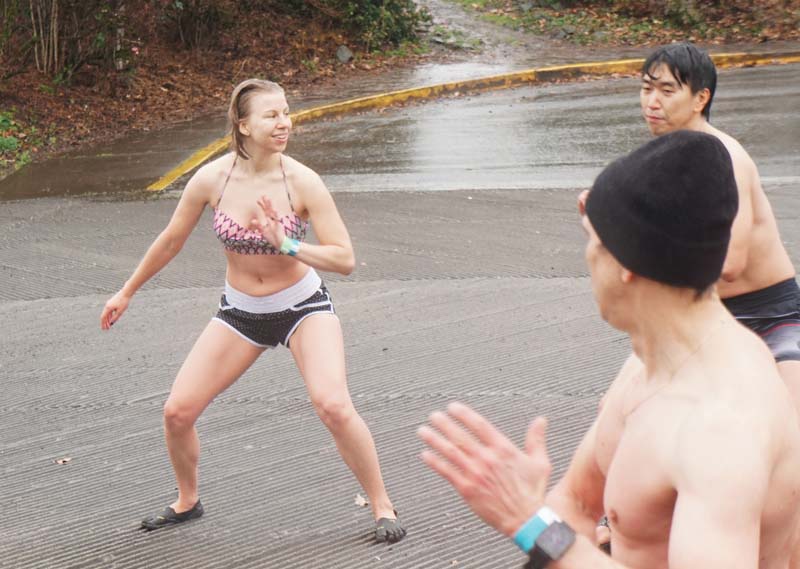

Perhaps grateful to have simply survived the experience, a group of Valentine’s Day Dip participants gathered in a circle to dance following their sojourn in the chilly waters of the Willamette River.

Risk Assessment

I’ve had the opportunity to spend a lot of time around firefighters throughout my career, and occasionally I glean a bit of wisdom from their hard-won experience. I once asked a group of firefighters how they make that fateful decision, to run into a burning building, and they gave me a surprisingly straightforward answer: “Risk a little to save a little. Risk a lot to save a lot.”

That idea has stuck with me ever since, and influences my aeronautical decision-making process to this day: Risks should be proportionate to the goal that might be achieved by taking them. So, I began by assessing the value of my mission: It would provide aerial video to support HAP’s future marketing efforts, but there were already several terrestrial video crews covering the event, so even if I decided not to fly, they would still have plenty of good coverage.

After that, I considered the hazards I had to overcome to achieve that result. The Phantom 4 is not officially weatherproof, but the vents for the speed controls are located on the underside of the limbs, reducing the risk of water intrusion. Also, the propellers turning at 5,000 rpm tend to push rain drops away from the aircraft.

Next, I had to assess the possibility that a drop of water would land on the lens, spoiling any video I captured, even if I did safely complete the flight. On the Phantom 4, the camera gimbal is slung directly underneath the airframe, providing some protection and, again, the propellers tend to fling water away.

In the final analysis, I judged it likely that I could fly safely, and that the lens would remain free from water for the brief time my machine was in the air. And then, I knocked that estimate down a little bit to account for my own penchant for feeling invulnerable.

A tent with hot coffee and pastries welcomed Valentine’s Day Dip participants and provided them a place to shelter after their plunge in the chilly Willamette River.

Two portable saunas were on hand to help “dippers” in the

An intrepid member of one of the ground-based video crews covering the Valentine’s Day Dip mounts a GoPro on a tripod and sets it at water level to capture a unique perspective of the action, as the participants splash into the Willamette. In the background, a safety kayaker keeps watch.

Best Judgment

In the final few moments before the crowd rushed the chilly river, the wind picking up slightly. I made my decision. My drone would stay inside its carrying case, and HAP would have to make do without any aerials of the event. In the end, I determined that the gains—a few seconds of video in the finished production, were too small and, although the risk of a failure was slight, in my estimation the consequences of failure would be significant.

Most likely, the Phantom 4 would have ended up at the bottom of the Willamette River, and hundreds of people would have witnessed a drone crash—not the best advertisement for a burgeoning industry like ours. And, if I did crash, what was I going to say? I was fully aware of the fact that the aircraft was not rated to fly in that weather, so crashing would be just one more painful demonstration of how my own sense of invulnerability caused me to make a bad choice.

That said, other circumstances would prompt me to make a different choice. If the weather was exactly the same but I was assisting firefighters at the scene of a residential blaze, I would put the bird up without a second thought. Sure, it could be destroyed, but the aerial perspective might save a life. Also, a drop of water on the lens would be irrelevant since first responders need information, not pretty pictures.

There was another question that occurred to me, as well: What if another drone pilot had been on the scene and decided to fly the same type of aircraft under those conditions? I would not have judged too harshly, I hope. I’d like to talk to that pilot to understand the decision-making process, and I might offer a word of caution if I had the sense that it was a new pilot, but then I would stand by and serve as a visual observer, if needed.

As pilots, it is incumbent on each of us to use our own best judgment, and when it comes to marginal cases, professionals can and will disagree. Just make sure that safety is always your top priority, and that you understand the level of risk you are facing relative to the value of the outcome you hope to achieve.–Text & photos by Patrick Sherman