Check out this article from https://www.yahoo.com/tech/drone-is-a-newish-term-for-a-very-old-concept-a-88576262689.html

Drone is a newish term for a very old concept: a remote-controlled aircraft. My kids had remote-controlled toy helicopters when they were 5, but nobody called them drones.

Drones are remote-controlled vehicles that are much smarter than the toys we’re used to. There are military drones, which can spy or even fight for us. And hobbyist drones, which require assembly and every-single-weekend dedication.

Now there are consumer drones, which you can fly the day you buy. For $300, you can get the first popular flying drone, the Parrot AR.Drone. You fly it using your phone as a remote control. The AR.Drone is smart enough to land and take off by itself, to hover in one place when you take your hands off the controls, and even to stop flying away from you if it goes out of range from your phone. It takes pictures and videos, and it’s a lot of fun.

But for $1,300, you can buy something that’s far more useful — and genuinely mind-blowing. Meet the Phantom 2 Vision+.

It’s made by DJI, the 800-pound gorilla of the consumer-drone industry. The “Vision” refers to the built-in camera, which takes pictures and captures hi-def video in flight. And the “+” refers to the camera’s three-axis gimbal (like a universal joint), a new feature that keeps your footage incrediblysmooth and stable, no matter what the drone itself is doing.

(You can buy the same drone without a camera for $700. That model is called just the the Phantom 2. You can put your own GoPro on it. Or you can buy it with a nonpivoting camera for $1,000: the Phantom 2 Vision.)

The new Phantom is far simpler to set up and operate than the hobbyist quadcopters of old. The battery lasts longer — about 25 minutes of flight on a charge. The battery also snaps neatly into the body; you don’t have to connect little wires like you do with most of the first-generation drones.

You get a proper remote control, with physical joysticks that you can use by feel, so you can keep your eye on the drone instead of on your remote. And as with the Parrot, if you let go, the drone hovers, no matter where it is or how high it is.

The Phantom is not, however, simple enough. The first problem is the documentation: a blizzard of manuals, fold-out guides and reference cards — 10 of them — written confusingly. They seem to assume that you’re already a drone enthusiast. There’s a lot to get familiar with. Here’s a quick guide:

The hardware

There are four parts to your Phantom system: the quadcopter itself; the remote control; the range extender, which gives you the Phantom’s extraordinary range of half a mile; and your own smartphone. A spring-loaded gripper, also attached to the remote, holds your phone.

While you fly, the phone’s screen shows you what the drone’s camera is seeing. The phone app also lets you start and stop video recording and lets you tilt the camera up to 90 degrees, from straight ahead to straight down. The videos are recorded, without sound, on a MicroSD memory card. The Phantom comes with a 4-gigabyte card.

Each component has its own battery, and all four must be charged for each flight. The quadcopter battery requires the supplied AC adapter; the range extender charges from a USB cable; the remote control takes four AA batteries.

It’s a lot of pieces and batteries. Why can’t the range extender be built right into the remote, for example?

Got that? Now on to flight

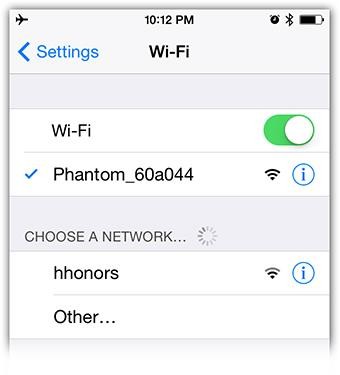

Once you’ve got the hardware sorted out, the next step involves downloading the free DJI app for your iPhone or Android phone and pairing it with your drone. This process, too, is a little user-hostile: You turn on the drone. Then, in your phone’s WiFi settings, choose the WiFi network name being broadcast by the drone itself. It can take several minutes for this network name to appear. (The Parrot AR.Drone pairs with a phone the same way.)

To take off, you signal the drone that you want to go by pushing both joysticks down and inward simultaneously. To fly, the left joystick controls altitude (push the stick up or down) and rotation (push the stick left or right); the right joystick tips the drone forward or backward, left or right — in other words, it’s the four-direction accelerator pedal.

The remote control handles manual flight, but the phone app is packed with other features. You use it to take stills and videos, to control the frame rate and quality of them, to monitor your altitude and GPS status, to view the names of the roads beneath you, and so on. Now in beta testing is a software update that lets you preprogram routes so the drone can fly missions automatically, without any remote control at all.

Preflight jitters

Getting familiar with everything was overwhelming. So before I tried flying the Phantom myself, I enlisted the aid of Peter Sachs, a drone advocate and experienced pilot, to join me on a local beach to show me the ropes. Having someone show you how to do all this is the best way to learn. It’s a truly new skill, and there are a lot of moving parts. Which can crash.

Peter, who’s not affiliated with DJI, owns two Phantoms, and he flies them almost every day. (He’s a private investigator by trade, but he says he doesn’t use drones in his work: “That would be cheating.”)

He’s never crashed one or lost a Phantom, but then again, he’s a very conservative flyer. He takes off and lands very gently; he urges everyone to stand well back; and he lands as soon as the first low-battery alarm sounds (at 30 percent charge remaining).

He’s never lost a drone, either, but that may be because of the Phantom’s brilliant Return to Home feature: if it loses signal with your remote for any reason — your remote battery dies, you fly too far away, whatever — its GPS makes an executive decision to return to the precise spot where it took off. That’s an incredible safety net for your $1,300 helicopter.

We tried out that feature, too: We just turned off the remote. The phone screen said “Coming Home,” and sure enough — the thing flew back to us, nice and high (it can’t see buildings or trees), and then landed at our feet. Peter told me that some pilots conclude everyflight that way.

Anyway. The point is, all of my quibbles about instructions and complexity evaporated once I got to fly this thing.

To the skies!

It is amazing.

The Phantom can fly ridiculously high and blazingly fast. And yet, controlling it is unbelievablyeasy, graceful and precise. The response to each move of your joystick is instantaneous and predictable; it’s as though the calibration of the controls have been designed to compensate for human behavior, instincts and lag time.

Some people like to fly the Phantom by watching it from the ground. Others keep their eyes glued to the phone screen, as though the whole thing is a video game.

It’s absolutely thrilling just to fly the Phantom, as I discovered during a few more days of flying on my own. You can really make it zoom, really make it skyrocket — and you get to see what it’s seeing, right there on your phone. It’s your eye in the sky.

But it can be much more than a glorified toy. There’s a huge list of ways that the Phantom can be useful. Photographers, of course, are going nuts over these machines; drones provide vantage points and angles that have never been possible or realistic before.

Here, for example, is some typical Phantom video. The footage isn’t as beautiful or professional as what you’d get from, say, a GoPro camera; it’s a little more cellphoney and flat. But it’s great for many purposes:

If you think about it, almost the entire history of photography and video has tapped maybe two percent of the world’s visual possibilities; it’s all been anchored to the ground, in two-dimensional space. Putting your camera on a drone opens up the third dimension, gigantically multiplying the possibilities of space and angle.

People are also using these things for search-and-rescue in dangerous situations (fire departments, for example); safely inspecting bridges, pipelines, and skyscrapers; tracking wildlife (or poachers thereof); farming; environmental inspection; surveillance and law enforcement; and, maybe someday, deliveries of everything from pizza to Amazon packages.

There’s a lot that we, as a society and a country, still have to work out. As drones become more popular and plentiful, what will happen when the skies are full of them? And who’s going to regulate them? (Peter Sachs tells me that there are actually no laws on the books about consumer drones. On his drone law blog, he bristles about the FAA sending cease-and-desist letters to model aircraft pilots, when, he says, it has no legal authority to do so.)

But never mind all that. For now, there’s plenty of space to fly your own drone. And thanks to the Phantom 2 Vision+, it’s now possible for ordinary people to do that — without a license, without mechanical expertise, and with only a few minutes of practice. No, there’s no $1,300 technology that lets you fly, hover and swoop — but an airborne camera that you control with inch-by-inch precision comes deliciously close.